Five Not-Quite Theses on the Treadmill

"Were 'In the Penal Colony' to be written today, Kafka could only be speaking of an exercise machine. Instead of the sentence to be tattooed on its victims, the machine would inscribe lines of numbers. So many calories, so many miles, so many watts, so many laps."

So begins Mark Greif's classic essay "Against Exercise," which first appeared in the journal n+1 twenty years ago.

"Modern exercise makes you acknowledge the machine operating inside yourself," Greif continues. "Nothing can make you believe we harbor nostalgia for factory work but a modern gym. The lever of the die press no longer commands us at work. But with the gym we import vestiges of the leftover equipment of industry to our leisure. We leave the office, and put the conveyor belt under our feet, and run as if chased by devils."

The treadmill. Gyms are filled with rows and rows of these absurd devices, on which we run and run and run and run and go nowhere, unable to look away from a dashboard that reminds us of "data" — speed and incline and duration and heart rate — that are at best approximations and at worst meaningless inaccuracies. Well before the launch of the first Fitbit, Greif had identified the 21st century's great push towards "optimization" via exercise, not just in the fitness tracker but in the larger machinery of fitness — the Nautilus machine, the treadmill.

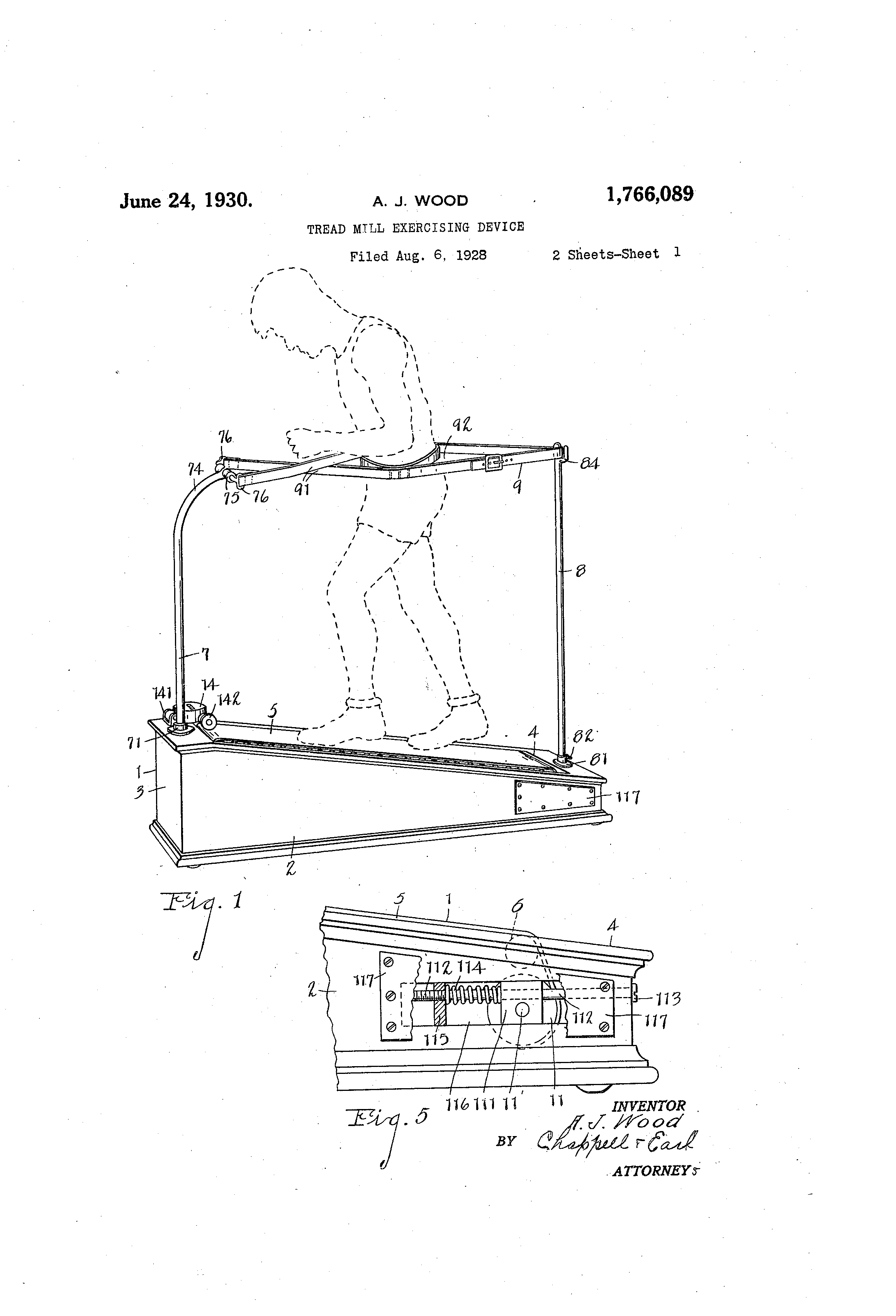

His invocation of Franz Kafka's short story seems so apt when one traces the history of the treadmill, as many commentators often do, to prison labor. The device, so this story goes, was invented in the mid-nineteenth century by William Cubitt.

His “Tread-Wheel,” which was described in the 1822 edition of Rules for the Government of Gaols, Houses of Correction, and Penitentiaries (published by the British Society for the Improvement of Prison Discipline and for the Reformation of Juvenile Offenders), was presented as a way for prisoners to put in an honest day’s labor. Prisoners used treadmills in groups, with up to two dozen convicts working a single machine, usually grinding grain or pumping water, sometimes for as long as eight hours at a stretch. They’d do so "by means of steps … the gang of prisoners ascend[ing] at one end … their combined weight acting upon every successive stepping board, precisely as a stream upon the float-boards of a water wheel."

This wasn't actually the first "tread wheel" — the Romans used a similar device to power a winch of sorts to aid in the moving of heavy stones. But if you're going to frame the treadmill as a torture device — or, more broadly, frame exercise as part of the machinery of scientific management, of a trajectory that has brought us to digital Taylorism today — you can't really dwell too much on this ancient usage. You have to start your story in the work-house — the factory is the gym is the factory, in Grief's formulation.

To be fair, like the nineteenth century prison reformers who adopted the treadmill, our culture still link idleness and immorality — "diet culture" and "fitness culture" and hell, much of modern medicine are shot through with judgments about bodies and sin and sloth.

Oscar Wilde, imprisoned for "gross indecency" in 1895, was among those sentenced to hard labor that included the treadmill. As he wrote in his poem "The Ballad of Reading Gaol,"

We sewed the sacks, we broke the stones,

We turned the dusty drill:

We banged the tins, and bawled the hymns,

And sweated on the mill:

But in the heart of every man

Terror was lying still.

The terror of prison is the terror of hard labor is the terror of the treadmill.

The terror of the treadmill. James Hardie, who operated the treadmill at the Bellevue Penitentiary in New York City in the early 1820s, wrote of this aspect of the device as punishment. "It is constant and sufficiently sever; but it is its monotonous steadiness and not its severity, which constitutes its terror and frequently breaks down the obstinate spirit."

We're still sentenced to "hard labor" today, Greif contends — sentenced to do time on the "dreadmill," as some call it, where it's not just our bodies that are broken by the repetitive movements on the machine but our minds. Running on the treadmill is tortuous mentally.

It's not, actually. I mean, it can suck. But it's not torture. Come on.

I'm reluctant to subscribe to any of these stories as a runner — its own problematic identity, according to Greif: "The gym is in this sense more polite than the narrow riverside, street, or nature path, wherever runners take over shared places for themselves. With his speed and narcissistic intensity the runner corrupts the space of walking, thinking, talking, and everyday contact. He jostles the idler out of his reverie. He races between pedestrians in conversation. The runner can oppose sociability and solitude by publicly sweating on them."

Many runners (perhaps in their sociopathic commitment to wreck public space, right?) will sneer at the treadmill. Many will point out that it's not quite the same physiologically as running outdoors – there's no wind resistance, for starters; the belt shortens one's stride. But even without citing scientific research, some runners simply view the treadmill as inferior to an outdoor run. And sure, I'd rather run outdoors too, except on days when I'd rather not.

There are many good reasons to run on a treadmill — reasons like "convenience" that I'm sure Greif would readily dismiss. And as we experience more and more effects from global climate change — hotter temperatures, severe storms, air pollution, and so on — I think we might have to reevaluate what (and where) "counts" as a run. I mean, it's spring here in the northern hemisphere, and while I'm planning to make the most of some gorgeous, sunny weather, I know that I'm only months away from the heat and humidity driving my training indoors.

It should be no surprise perhaps that running on a treadmill is pathologized. If one history of the device is, in certain circles at least, traced to nineteenth century prisons, another story readily links it illness – to mid-twentieth century medical laboratories and the research into what had become the leading cause of death in post-war America: heart disease. (I wrote about this in my series of stories on the history of the heart rate monitor, remember?) In order to evaluate patients' heart rates in conditions other than "at rest," some sort of exercising device needed to be built — and the treadmill was re-invented to do just that.

The treadmill, in this story, is not a torture device but a crucial piece of health technology; the human not a prisoner, but a test subject.

It's still hardly a technology of liberation.

The earliest known use of the phrase "hamster wheel" also dates to the mid-twentieth century — an advertisement in The LA Times in 1949. The invention of the device dates back perhaps fifty years before that. Rodents in laboratories — mice and rats in particular — have long been given wheels on which to exercise, otherwise trapped in their cages. These wheels are used to measure and monitor their activity levels, but have long been seen as an artifact of their captivity. Perhaps the hamster wheel is actually the technological metaphor Greif and others are looking for. Like the treadmill, the wheel spins and spins and one runs and runs and goes nowhere. Yet what else is there to do — the environment is shaped in such a way that the wheel is a compulsion. A neurosis, even.

And yet...

Dutch scientists Johanna H. Meijer and Yuri Robbers conducted a study, leaving a hamster wheels in the wild. They found that wild mice also ran on them, even when there was no extrinsic reward for doing so. (That is, even when there was no food. Also taking the wheel for a spin: shrews, rats, frogs, and snails, although the latter was deemed "haphazard" and removed from the final analysis.)

Why the hell do wild creatures choose to run on a hamster wheel? We don't know, the scientists admit. Perhaps it's fun – or somehow in some way still "rewarding." Even if it's repetitive. Even if it's invariant. Even if there's no forward motion, no goal, no reason to run. Perhaps it's play.

Perhaps no one told them that the treadmill is meant to be punishment.

Thanks for reading Second Breakfast. Please consider becoming a paid subscriber. Doing so gives me the time and space to pull together a bunch of disparate ideas that may or may not make sense, but with your support, someday might.