A History of Breakfast (and the Case for Leftovers)

I always find great comfort in knowing that things are "socially constructed," that our beliefs and practices have histories, that despite their seeming to be all-pervasive and ever-enduring that they're malleable. Things change. We can change.

Breakfasts change.

Breakfast might seem like a meal that we absolutely must eat and must eat in a certain way — with certain food items at a certain time. "It's the most important meal of the day," we're often told. (Of course, we're also told that dinner is the most meal of the day insofar as one must make sure one has quality "family time." This meal is important for children's acquisition of language, we're told, not to mention their learning of "good manners." And all that's before we get into the things we're told to eat, we're supposed to eat.)

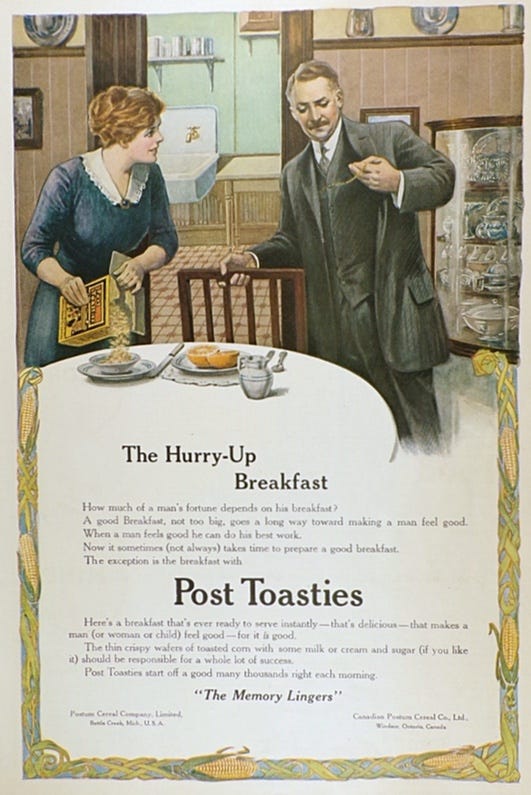

Much of the emphasis on the importance of breakfast stresses the necessity of replenishing one's body in the morning after a long night's sleep — you know, breaking the fast. But there's something about breakfast that, when you scrutinize it, underscores how much of our expectations around eating are cultural, not simply nutritional. Breakfast has a certain morality to it, and not merely because the purveyors of cereal in the nineteenth century were health reformers who believed that a grain-based breakfast was a dietary and spiritual solution to a nation suffering from dyspepsia.

Breakfast — as we think of the meal today, that is — has its origins in part in the Industrial Revolution, as the new expectations around labor under capitalism altered the ways in which people ate. Dinner, not supper or lunch, became the main meal of the day. Breakfast was something to be consumed before leaving for the factory — and with the expansion of public schooling, before leaving for school.

Breakfast wasn't a new meal, of course. People wake up hungry; people eat in the mornings. Often, that first meal would be leftovers from the day before. Sometimes, depending on the location and the labor to be done, breakfast would be pretty substantial, perhaps even the largest meal of the day.

There are many breakfast items that have a long history in the US, that pre-date the industrialized breakfast expectations: pancakes, muffins, doughnuts, biscuits, ham, coffee. Sometimes the remnants from this meal were packaged up to be snacked on midday.

But the nineteenth century version of the "wellness" industry decided that these were the wrong sorts of things to eat in the morning. Breakfast, health reformers believed, needed be reframed and reformulated in such a way as to improve people's digestion and of course, their lives. (And, as wellness culture is wont to do, reframed and reformulated in such a way as to make a lot of money.)

It is hard to say which came first: the new breakfast ideal or the products that helped Americans live up to it. Whatever the case, breakfast would never be the same after business-minded salubrity seekers got a hold of it. They made the once decadent morning meal more compatible with the increasingly sedentary late-nineteenth and early-twentieth-century lifestyle, and because their products required little or no preparation and were virtually ready to eat, these entrepreneurs also found themselves developing a new kind of commodity: convenience. Convenience accommodated a faster-paced society; it was good for the busy, career-driven consumer because it meant less time cooking and eating and more time working and earning. Much like lunch, breakfast ultimately owes its shape to the powerful forces of business. Business incentives drove entrepreneurs to create new products, grain producers to seek more profitable outlets than livestock agriculture for their goods, and middle-class Americans to simplify their morning routine in order to get to work. — Abigail Carroll, Three Squares: The Invention of the American Meal

There was little agreement, however, on what a "healthy breakfast" might entail. Nor was there universal agreement, it should be noted, on what constituted "the wrong thing" to eat — was bread, for example, good or bad?

Since we've moved to NYC, I've had to adjust how much I cook and bake. In part, it's because Kin is going into the office every day, so I'm the only one home needing to eat during the day. Most of the dinners I make serve four, so leftovers accumulate in the fridge for a few days until it's "leftovers for dinner!" and all the containers get pulled out onto the counter and we each get to decide what we'll put on our plates and reheat in the microwave. (Organizational tip: I have a dry erase board on the fridge where I list the leftovers, along with the date they need to be eaten by.)

For a long time, I frowned upon leftovers. (I think this is a remnant of childhood food traumas, where my mom would roast some meat on Sunday — and I didn't like meat at all — and we'd eat some version of leftovers for the next few nights. It'd be prepped in different ways, sure, with the last night of roast meat often a curry — my dad would make some racist statement about the spices covering up rotting meat, but frankly the curries were always my favorite.)

It's funny because while many of us will eat the same thing for breakfast day in and day out and day in and day out, the idea of eating the same thing for dinner night after night is frowned upon — it's not just boring but (again with the moralizing and food!) a domestic failure.

, in her cookbook Now & Again, reframes the idea of leftovers with recipes that come from a "place of plenty, from the feeling that there is more than enough." Cook with abundance in mind, she says. Plan for leftovers and be open to turning them into entirely new dishes.

Eat leftovers for breakfast. Just reheat dinner in the microwave. Anything can become a "hash," if you reheat it in a cast iron skillet and fry or poach an egg for the top. Anything can be breakfast sandwich if you serve it on a roll with some melted cheese. Anything can become a waffle if you reheat it in a waffle iron. Don't let W. K. Kellogg et al guilt you into only eating cereal for breakfast — man was a bookkeeper, not a nutritionist, after all. And even if he was…