About Audrey: The Athlete

Or, how I learned to move my body

Although many subscribers here know me for my work in education technology — my writings at Hack Education, my HEWN newsletter, my books and talks on the topic — as this is a new newsletter on new topics with new subscribers, I thought it might be best to introduce myself a bit and situate myself. Even for those who do know me, on- or offline, some of this story is probably unfamiliar. Indeed, it's not just writing about sports and fitness technologies that's new for me; my seeing myself as an athlete is a recent development.

It's a development born in part of the pandemic, as like many people I found myself concerned about my health, mentally and physically. The death of my son demolished me. My heart, as I wrote in one of the last HEWNs, was quite literally broken: a routine doctor's visit found a heart murmur; bloodwork showed I was ridiculously anemic; I was diagnosed with fibroids. After blood transfusions, surgery, a brief stint on some experimental medication, and a lot of supplemental iron, I found myself gradually having more strength.

For the first time in my life, I was "active" — there was something about the combination of illness, trauma, and aging that made me realize that I had to get up and move or else I was going to physically (and mentally) crumble.

Kin and I adopted a dog and started walking around Lake Merritt — about 4 miles — every morning. One of my best friends, Margarita, is a yoga teacher in Portland, and I started taking lessons from her via Zoom twice a week. Inspired by my friend Shana, I decided to start powerlifting and signed up for a "learn to lift" session at Bay Strength, a local gym that had opened an outdoor space, full of squat racks, while indoor gyms remained closed.

Bay Strength changed my life.

I lift twice a week: typically squats and bench press on Tuesdays and deadlifts and overhead press on Thursdays. It's all barbells in a queer-friendly, anti-diet culture, pro-body-autonomy gym — there is no way I can replace it now that we’re moving, but I am determined to keep lifting. I can squat more than my body weight; soon I'll be able to out-deadlift Adele — something that's been a goal since she had that interview with Oprah.

I haven't hit that goal yet (I tell myself) because I started running at the beginning of 2022. I did the Couch to 5K program, culminating in my first race at the annual Oakland Running Festival. This year at that same event, I ran my first half marathon (in less than 2 hours!). I ran a second one six weeks later (shaving 3 minutes off my time!).

I'm a "multi-sport athlete," Coach KB tells me. I never ever imagined such a thing for myself.

I was decidedly un-athletic as a child. My mother, although obsessed with her weight, wasn't particularly active. (She is now — walking, strength training, swimming. Go Mom!)

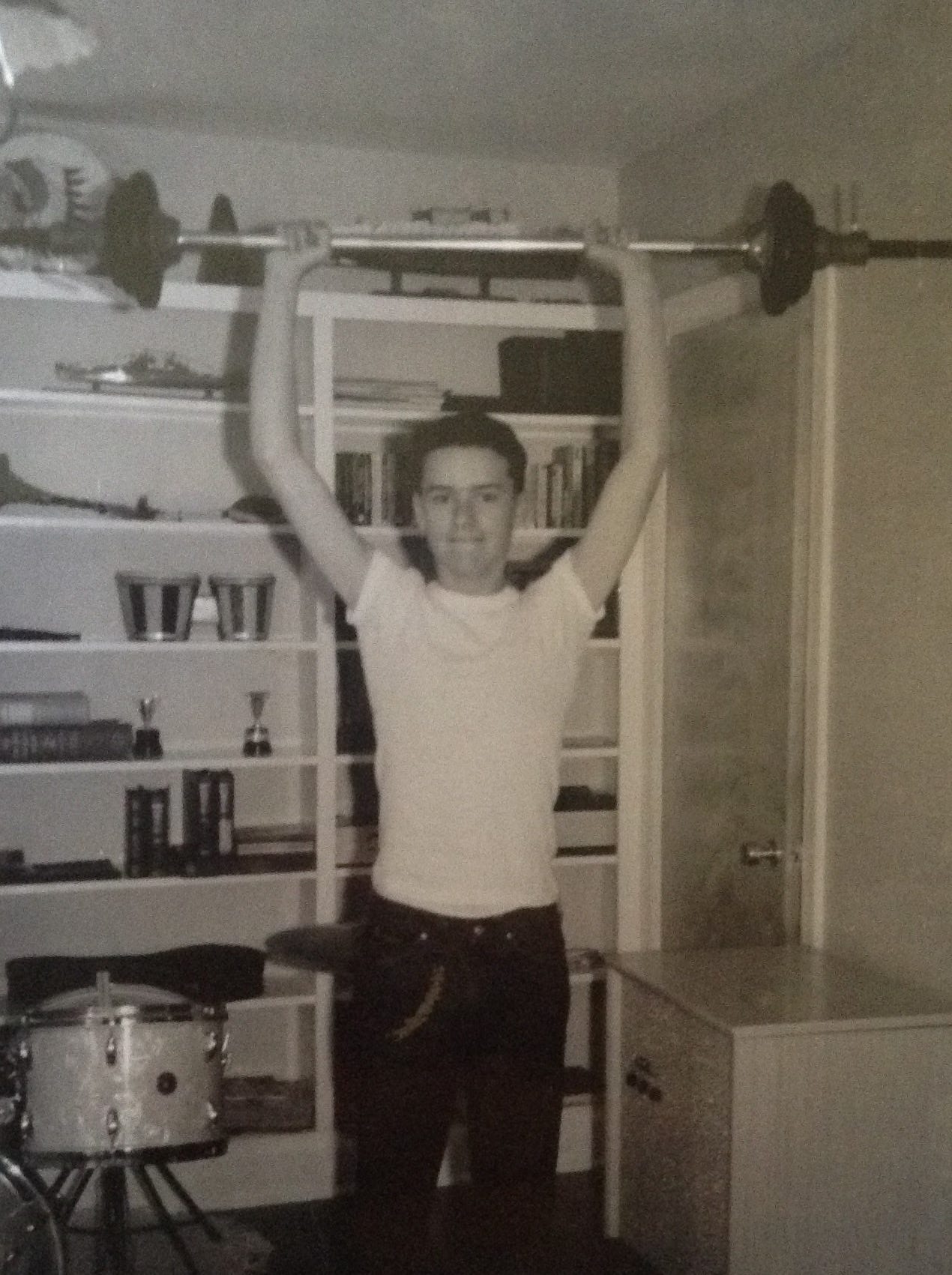

My father was even less so active (and I will have more to say in a subsequent essay about his disordered eating). He had severely broken his leg in college and despite several surgeries and plates and pins, the injury rendered him ineligible for the draft. It left him with a massive scar and a lifetime of pain (and guilt and shame as his friends went off to fight and die in Vietnam), something that he'd medicate every night with a lot of scotch and soda. A lot of scotch and soda.

Perhaps it was his traumatic injury in PE that made my own PE experiences so awful — epigenetics or something. Ha. Nah. Mine were awful for my own reasons, the main one being my terrible eyesight.

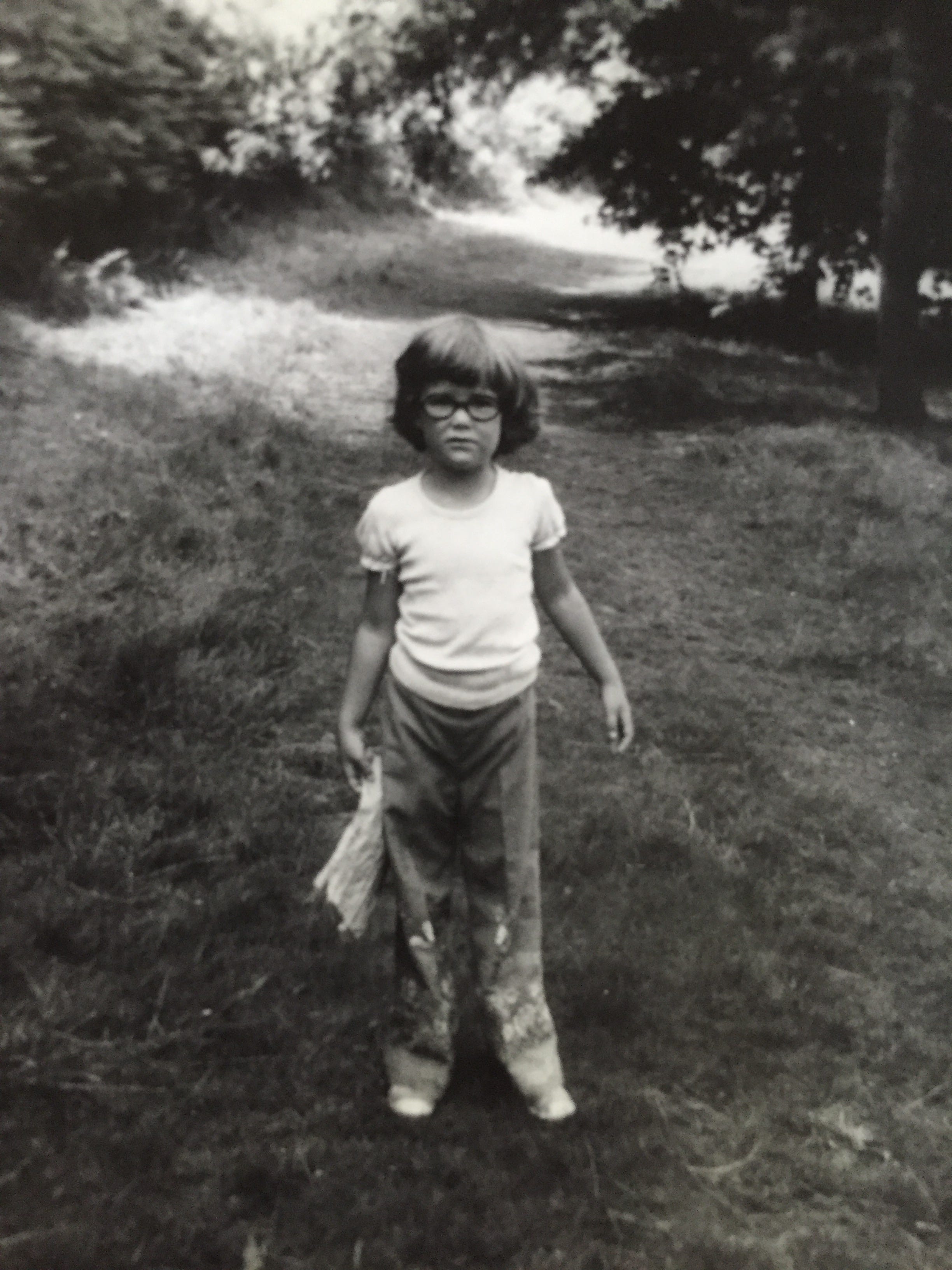

When my mom took me to register for kindergarten I couldn't read the sign they used for the cursory eye exam. Hell, I couldn't even see the sign. A trip to the eye doctor confirmed it: I needed glasses. Age 4. My mom said I marveled on the trip home wearing them that the trees had leaves, that there were stop lights. Apocryphal, I reckon as I'm sure I knew those things from books, which I read with the pages as close to my face as possible.

Even with glasses (and since eighth grade, contact lenses), my eyesight isn't corrected to anywhere near 20-20 vision. I cannot read anything below the first line on eye-chart, even with my contacts in. I navigate the world the best I can; but as I sometimes struggle to see, quite literally, where I'm going, I haven't always had the confidence to move around. This is compounded by an insight revealed by one eye doctor, who told me that I'm left-eye dominant; as I'm right-handed, it means that I struggle with coordination; and catching a ball — even if I could see it better as it buzzed towards me — is near impossible. (Ostensibly this should make me good at hitting a baseball, but I'd have to be able to see the ball coming with that “strong” left eye as I waited with the bat pulled back against my right shoulder.)

You know the story. Many of us do: last to be picked for teams in PE class; mocked for my inability to catch, throw, run, jump. I found myself limited in even the one activity I enjoyed — swimming — because I couldn't see where the hell I was going.

I just figured I was never meant to be athletic; I put my energy into being cerebral instead. It was fine. Until I hit 50 and my body decided that no, it wasn't.

But let's be clear: no one really pressured me into sports because, thanks to genetics more than anything, I have always resided in a straight-size body. No one in my family ever pressured me to play sports. (My brother, on the other hand, sought an appointment to one of the military academies, and as such — and because of gendered expectations that, as a girl, I could eschew — he did go out for cross-country skiing in high school.)

When I was six or so, my mom signed me up for ballet class. On the first day, we were told to skip across the room. I couldn't skip. As I spent hours playing in the backyard with my next door neighbor Rebecca, pretending to be horses, I could gallop. But I could not skip. The teacher Mrs. Buckingham sneered, and the class laughed at me, and I vowed to never go back.

I'm sure I could have figured it out, if I'd be coached with love and support. I know now, despite the story I always told myself, that it's not as simple as "I just suck at sports." Rather no one cared, no one bothered to help me find my strength. And I never had the confidence to even try to get good at things, in part because I quite literally couldn’t see what I was doing. Even if I couldn’t see other people, I could hear the laughter — or I imagined I could.

I still can't see. But what I've developed in the last few years — in addition to some badass post-menopausal musculature and a helluva lot of confidence — is better proprioception. I have a sense of my body in space, a sense of my physical power and potential. I’m still learning what to do with it.