Computing versus Democracy

The Gates Foundation, we learned this week, is backing away from its environmental efforts, slashing staff and funding for projects that sought in part to address global climate change. Bill Gates is "retooling his empire for the Trump era," as The New York Times put it. No mention in that story of AI, surely one reason why, as the article notes in passing, that the "demand for electricity is rising sharply" – a phrasing that relies on the passive voice construction to obscure the deep ties between the computing and the fossil fuel industries, between Gates's immense wealth and the destruction of the planet.

We are in the midst of a "war on the future," as Jamelle Bouie put it – a war against education, the environment, science, healthcare, a war against our very survival. And philanthropy won't save us. Indeed, the purpose of philanthropy has never been thus. At the end of the day, it's always been just a tax dodge.

I do confess, however: I am always sort of shocked that, somewhere along the way, we forgot that Bill Gates and Microsoft are the villains in this story-line.

This couldn't have been more clear in the 1980s and 1990s, I reckon – the US government's anti-trust lawsuit against Microsoft was perhaps the culmination of this widely held belief that the company was just bad. The lawsuit challenged Microsoft's monopolistic behavior with regard to how its operating system's handled (or not) competitors' web browsers. But there were other signals that Gates's and Microsoft' dominance were problematic economically, technologically, culturally. Microsoft was the Borg, for crying out loud. And when Bill Gates became the richest man in the world in the mid-1990s, both he and his software company were reviled. Reviled.

Of course, Gates stepped down as CEO of Microsoft soon after to focus on his philanthropic efforts, and he's been incredibly successful at laundering his reputation. His name is probably more synonymous now with his foundation's work than with his company's shady and litigious business practices or its shoddy, bloated software. That's what being a billionaire gets you, I guess. (Or once got you. I like to believe this is one of the things that makes Mark Zuckerberg so damn mad: he's rich and ostensibly "charitable," and everyone still hates his guts.)

Some time in the final decades of the twentieth century – was it before or after that anti-trust lawsuit, I'm not sure – American society gave up on taxing the wealthy, gave up on funding and extending the New Deal security and stability to everyone – lured by the false promise, no doubt, that big business and philanthropy would handle the things that Ronald Reagan and Milton Friedman insisted government could not. We were all told that, sure, there'd be no more social safety net, but everything would be okay: we had computers now, we had the Internet.

Rather than vanquishing Microsoft (or tech billionaires), we've bent many of our practices towards its products, its ideology. Microsoft Office and its various competitors' clones have become utterly ubiquitous in the white-collar workplace and in the classroom, and we've completely surrendered "work" to the company's mundane vision of productivity software – tools that produce "bullshit jobs" in turn; tools that, it's worth noting, have done nothing much at all to boost actual productivity (at least as economists measure it) in the intervening decades. Somehow we're all busier than ever clicking on things; but we're not getting much more done. We're all relatively poorer too, while billionaires like Bill Gates are richer than ever before.

Long before this country's recent turn toward techno-autocracy, Bill Gates has wielded his power – the power of an oligarch, which to be crystal clear is fundamentally an anti-democratic power – to "reform" public education; and certainly no one else has been as influential in shaping American education policy, bending all policy towards technology policy – whether in instruction or assessment. Bill Gates gave us InBloom. Charter schools. The Common Core. He gave us Sal Khan and Khan Academy, the latter of which is now synonymous with education technology and certainly with AI-as-instruction. And what a coincidence: Khan Academy's AI product Khanmigo runs on ChatGPT, the main product of OpenAI, whose largest funder is Microsoft.

We live in the future that Bill built; and it's a future that will never challenge oligarchy, because – I hope people will someday start to notice – computing technology itself has embraced and enabled neoliberalism, has accelerated inequality and autocracy. The industry has explicitly targeted some of the pillars of democracy for "disruption": journalism most famously, but also so clearly public education.

The glitzy TED-talk future of individualized, video-based instruction and chatbot teachers is, of course, decades and decades and decades old now, so maybe we've just grown accustomed to its rollout. Much like Microsoft Office, a few buttons and commands just get moved around and relabeled every couple of years, and still everyone is compelled to buy a new license for the "upgrade."

Gates' vision and thus, his foundation's grant-funding patterns have been pretty consistent since its launch, with some of his language simply updated to match the latest hype cycle – what once was "adaptive learning" is now "AI." Since the late 1990s, he has dreamed of (and funded) a world of "personalized education," unlocked via algorithmically-driven content-delivery systems that enable "lifelong learners" to "move at their own pace" through standardized curricula, with immediate feedback from some sort of "pedagogical agent" – once upon a time from Clippy and now from a different ChatGPT interface.

None of Gates' vision for education has ever really worked as promised – I mean, look around, for crying out loud. But of course, it doesn't have to (and not simply because, under Trump, we're apparently no longer going to collect the data with which we might assess such things).

As with the whole "vibe coding" story-line that tech reporters have breathlessly repeated in recent weeks – that AI now magically "speaks things into existence" – these ed-tech reform initiatives just have to feel like they work. It's storytelling, not science. And to a certain extent, this is the rationale for almost all ed-tech initiatives, that always fall short of their revolutionary marketing promise. We have long pretended that sitting children in front of screens – be they film screens, TV screens, or computer screens – is good and necessary because it feels like the very most modern way to educate them.

But now, the screens will chat back, and we're being prompted and nudged to reject expertise, to reject knowledge, to reject research, to reject our own lived experience, to reject one another, and to embrace ignorance. It's more expedient for oligarchy, I reckon – and that's about it. That's the vibe: the very anti-democratic, anti-future vibe we're being presented with.

For Whom the Bell Tolls:

"The Labor Theory of AI" – Ben Tarnoff reviews Matteo Pasquinelli's The Eye of the Master.

Neil Selwyn questions whether GenAI will really be a labor-saving technology for teachers.

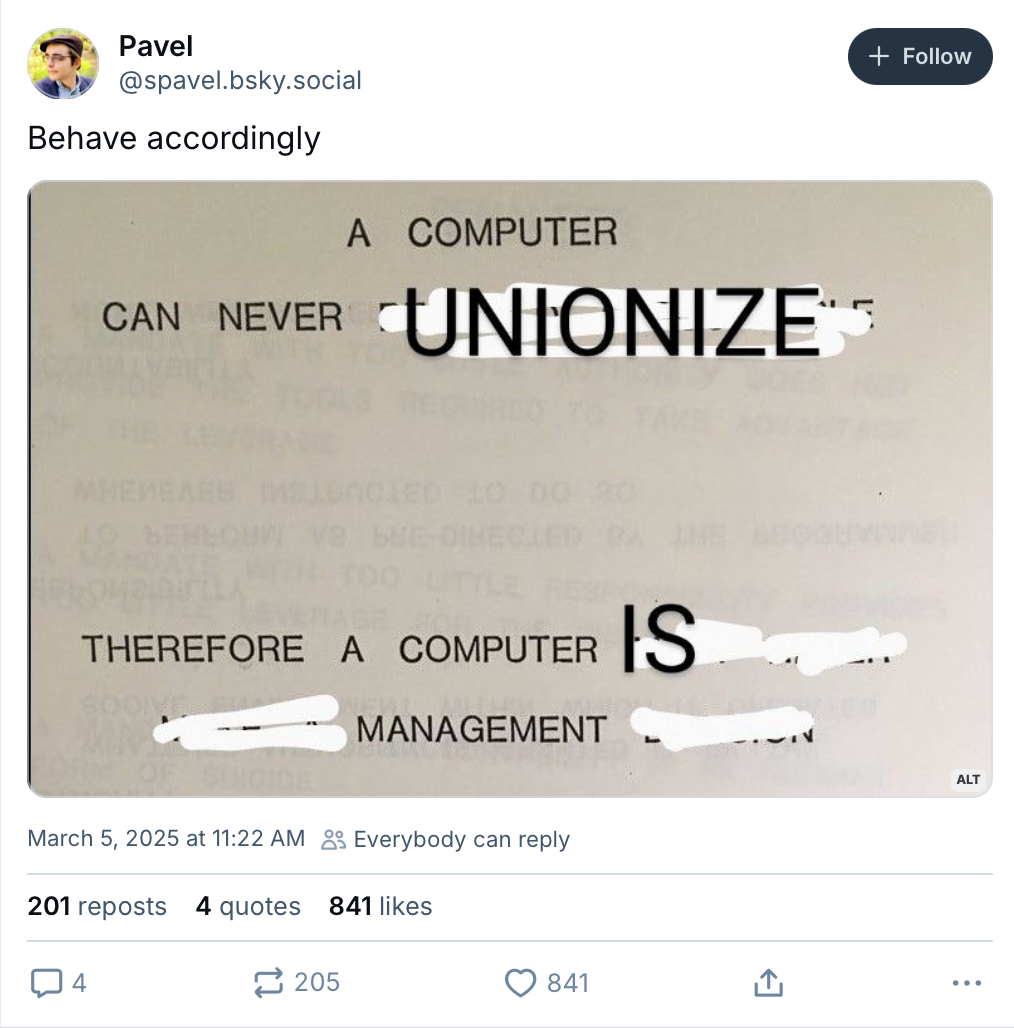

"Workers know exactly who AI will serve," writes Brian Merchant. Spoiler alert: management.

Just Asking Questions:

Liz Lopatto on "The questions ChatGPT shouldn’t answer":

The fundamental question of ethics — and arguably of all philosophy — is about how to live before you die. What is a good life? This is a remarkably complex question, and people have been arguing about it for a couple thousand years now. I cannot believe I have to explain this, but it is unbelievably stupid that OpenAI feels it can provide answers to these questions.

Questions matter. "The tests we are using to assess the intelligence of AI are missing an essential aspect of human inquiry — the query itself," writes historian Dan Cohen.

But we're focused instead on AI as Oracle – on the promise of the one true source of answers. It's no surprise, really. In an era of mis- and disinformation, with growing inequality and political instability, it seems too dangerous to ask questions, particularly to ask other people.

Just keep your head down. Click quietly. Comply.

Ed-Tech's Pigeons:

"It was like getting rats for an experiment" – how Character.AI built its chatbots by testing the AI on kids.

Kelli Maria Korducki on "The Cult of Baby Tech" – "I think they give people a sense of control over something that feels very uncertain."

Rob Nelson of the AI Log reviews John Warner's new book More Than Words.

"There’s a Good Chance Your Kid Uses AI to Cheat," Matt Barnum and Deepa Seetharaman write in The Wall Street Journal.

"Schools are surveilling kids to prevent gun violence or suicide. The lack of privacy comes at a cost," Claire Bryan and Sharon Lurye write in The Hechinger Report.

Ring the Alarm:

Tech journalist Taylor Lorenz reaffirmed for her audience this week that "Cell phone bans in schools don't work," dismissing with a real sneer the efforts to limit students' access to phones as unscientific "moral panic."

Moral panics, she argues, are just based on "feels" – "vibes," I guess, but not the good kind that you might use to code a Pac-Man clone. (It's really hard to keep all these vibes straight.)

"Reactionary hacks have been pushing the false narrative that social media and smartphones are leading to declining literacy and mental health problems," she writes. "It’s false, and it’s simply the latest iteration of a long running freak out about the technology and media that young people are using." Not to worry, she assures her readers, drawing on the work of psychologist Christopher Ferguson (best known for his arguments that video games do not cause violence) who states "opinions will change once the old people die.” Golly, he sure seems nice.

The research on the effects of phones on students' grades and mental health isn't as clearcut as folks on any side of this debate might want you to believe. Social science rarely is – sorry, social scientists – in no small part because theories about human behaviors are hard to prove and harder still to falsify. And it's not so easy to run randomized control trials – ye olde "gold standard" of scientific research – on things like, say, students' phone usage, school policies, and mental health; so instead folks often statistics their way to the conclusions.

Listen, I'm no fan of Jonathan Haidt either. But one of the things that irks me the most in this ongoing debate – in addition to the death wish for old people that Lorenz repeats, and Ferguson's insistence that teachers who do report positive changes from cellphone bans are "full of crap" – is the flattening of this story into one where oppressive forces (be that schools or parents or principals or teachers) are doing harm to powerless kids by taking away their phones. It's a caricature of what's going on – a total caricature. If nothing else, there are plenty of examples of places – progressive schools – where students have asked for these kinds of policies, where they've actively debated and negotiated the terms of access and removal. But I can't help but notice the political bent of how often this gets framed: it's the schools – the government – that are the enemy of freedom here; never ever the technology industry.

It's an all too common tactic to disqualify any sort of criticism of technology by labeling it a "moral panic," as something motivated by emotion and by not reason or science. (According to Wikipedia, even Socrates – fucking Socrates – succumbed to a moral panic over technology, which really says everything you need to know about the emptiness of this catchphrase. And of Wikipedia, natch.) But shouting "moral panic" is the go-to rhetorical move of those defending digital technologies from any and all criticism. A moral panic means the criticism can be easily dismissed, not simply for its hysteria but for its "mob mentality." Frankly, it's an intellectually dishonest move – an ad hominem even – where the utterer doesn't have to engage in any of the substance or the nuance of a critique.

Any time you hear someone dismiss technology criticism – whether AI or cellphones or video games or social media – as mere "moral panic," know that this cyberlibertarian rhetoric serves to protect a powerful industry from regulatory oversight and often – notice a theme here? – from the will of the people.

You can’t enforce happiness. You can’t in the long run enforce anything. We don’t use force! All we need is adequate behavioral engineering.

– B. F. Skinner, Walden Two

I Don't Know How to Explain to You that You Should Care about Other People:

M. Gessen ends their op-ed on the Trump Administration's attacks on trans people by rejecting the typical closing paragraphs of this sort of thing, refusing to "finish with the standard exhortation: The attacks won’t stop here. If you don’t stand up for trans people or immigrants, there won’t be anyone left when they come for you."

But I find that line of argument both distasteful and disingenuous. It is undoubtedly true that the Trump administration won’t stop at denationalizing trans people, but it is also true that a majority of Americans are safe from these kinds of attacks, just as a majority of Germans were. The reason you should care about this is not that it could happen to you but that it is already happening to others. It is happening to people who, we claim, have rights just because we are human. It is happening to me, personally.

Thanks for subscribing to Second Breakfast. Please consider becoming a paid subscriber. Not only do you get to read all of Monday's newsletters – I mean, I didn't even bother to send you this week's if you hadn't coughed up some coinage – but you get the satisfaction of supporting a publication that refuses to auto-generate its verbiage and will never ever acquiesce to the authoritarian vision that Silicon Valley has for us – not just being enacted in DC today but across all of digital technology globally forever.