Banking on It

The news is bad. I mean that in both senses: "bad news" and "news, bad."

There's been much discussion this week of Trump's "university compact," his attempt to bribe the administrations at nine universities by promising them access to funding in exchange for agreeing to support Trump's political agenda. "The compact would require colleges to freeze tuition for five years, cap the enrollment of international students and commit to strict definitions of gender. Among other steps, universities would also be required to change their governance structures to prohibit anything that would 'punish, belittle and even spark violence against conservative ideas'," according to The New York Times.

Political scientist Henry Farrell argues that this is a demonstration of weakness, not strength. As he wrote in a NYT op-ed, "The struggle over regime change is about whether the aspiring authoritarians can subdue civil society. Their strategy is to play divide and conquer, rewarding friends and brutally punishing opponents. They win when society cracks, creating a self-enforcing set of expectations, in which everyone shuts up and complies because everyone expects everyone else to shut up and comply, too."

But as Timothy Burke observes, there are a fair number of people in positions of power – university leadership, corporate leadership, media leadership – who seem quite happy to comply, not so much as a full-throated embrace of fascism, as a smug sense of retribution: "They’re not seeing Trumpism for what it is nor what it is set to become, but instead as a kind of brief, evanescent opportunity for settling scores and putting themselves back in charge as they were meant to be." This moment provides them an opportunity to pushback on "DEI," most obviously, but all sort of changing norms around race, gender, religion, health, language, labor, behavior, bodies. – changes about which these people are so incredibly uncomfortable, so incredibly aggrieved.

I've written repeatedly about the role that venture capitalism plays in (mis)shaping education: through the funding of particular startups, through the manufacturing of particular narratives about school, for example. But it would be a mistake to reduce this to the efforts of the Marc Andreessens of the world. As we see in this new "university compact," the pressures here are coming from a different billionaire from a different financial sub-sector: namely Marc Rowan, the head of the private equity firm Apollo Global Management. (Apollo's education portfolio includes the University of Phoenix and McGraw-Hill.) While Rowan's efforts here are overtly ideological – he's mad about pro-Palestinian activism on college campuses, The NYT suggests – he is quite literally in the business of another ongoing shift in education (also ideological, I'd say): that is, its financialization. Here, the key outcome of school is profit for investors, with less and less and less of any semblance of academic mission – certainly no room for curiosity or play. Students, research, the very brick-and-mortar itself – these are all reduced to capital, to data, to transactions, and – investors hope – to value that can be extracted and monetized and sold off to the highest bidder.

Ideas – ideas that challenge the status quo of capitalism, sure, but really, any sort of new or critical thinking at all – are a threat. Trump provides an opportunity – and I can almost almost write this with a straight face – to put an end to ideas.

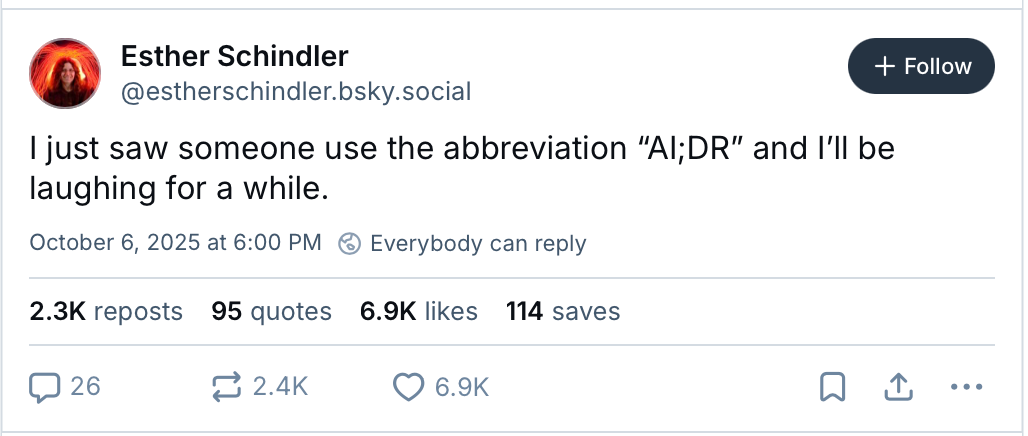

"AI" promises the end of ideas, the end of thinking, the end of professors and intellectuals (good riddance), the end of work (or at least, the end of organized labor) – and a future of endless wealth.

(I am reminded here of a quote by David Graeber, that "if working-class Bush voters tend to resent intellectuals more than they do the rich, then, the most likely reason is because they can imagine scenarios in which they might become rich, but cannot imagine one in which they, or any of their children, cold ever become members of the intelligentsia.")

...an authoritarian state with sufficient processing power could funnel every neural signal into government databases, creating a predictive algorithm for dissent.

It’s a terrifyingly simple formula: No physical violence required. No detention centers. No interrogation rooms.

Just a headset.

I am, I'll admit, always a little wary of stories that talk about China as the site of massive surveillance and techno-authoritarianism. In the US, at least, we've had massive surveillance as well; it's just been wielded for advertising rather than for explicit political control. But that appears to be changing, and US technology companies seem more than willing to acquiesce to the Trump Administration's demands – perhaps because they are aligned in their desire for a future of total information control.

Justin Reich writes in The Conversation about "What past education technology failures can teach us about the future of AI in schools." I am a big fan of the "let's look at history" approach to thinking about things, but in this case, I think it only gets us part of the way there; because what we are facing now isn't simply a new technology (an "arrival technology," Reich calls it); it is a new political and information environment, one that seeks the optimization of compliance and control, and one that is openly hostile to "literacy." (I suppose that cynics can say "oh, that's what school has always been," but that's not quite right either.) I think we do know some of the effects of "AI" on students – although perhaps not to the satisfaction of psychometricians – and they aren't good.

Related: Jason Koebler of 404 Media is asking for educators and librarians and others to "Help Us Investigate Book Bans and Educational Censorship Around America." Again, "AI" obfuscates a lot of this as it operates as an unaccountability machine: "the algorithm made me do it."

Some catharsic typing, from Delia Cai:

Literally I would respect it more if you clankers made like the much more normal financial villains and just accepted the cold, naked transactions between you vs. the rest of the world that you hope will tip you over on the side of invulnerability when The Big Quake comes, or at least imbue you with some nice memories of ordering omakase and flying Delta One before it hits.

You don’t know, or you can’t live with the nakedness of what you do all day, so instead you try to claw back some of that sexiness, courtesy of whatever lessons you’ve gotten summarized for you from some errant Wharton deck, with a minor in Corporate Memphis, because godfuckingdammit it can’t just be about the money and pwning your enemies and draining the world of all aspects of that annoying, frustrating, inefficient humanity of ours can it????? No, baby, you want the same basic shit we want: a sense of belonging and respect and delight—sometimes yes achievable by wearing a little thing that other people are also wearing; we sometimes call thosepeople friends, sweetheart, not your plastic narc necklace—and sure, let’s just admit it, there’s also a tiny trace of that Machiavellian satisfaction of getting other people’s priceless attention, god there’s truly nothing like it, is there. It makes you feel like a wizard king, and you cannot understand why they won’t just shut up and let you be wizard king. If only they understood the incredible satisfaction of being able to conjure an entire community—no wait, an entire universe—by merely by stringing together a combination of symbols on a screen somewhere. The power that has. Well, you don’t have to tell us. If only you knew that a simpler technology for that already exists. Personally, I recommend Moleskine.

A lot of people who really believed that, by being a prolific clicker and poster, they were powerful and innovative, are clearly enthralled with the glaze of "AI" because it soothes their self-doubt: "you're so clever," the machine-oracle assures them. "You're still relevant."

(But I'd like to add this: I absolutely loathe the epithet "clanker," as it seems to roll off the tongue of some folks with a bit too much racist gusto.)

Today's bird is the eastern phoebe, a small bird with a big head. I wanted to feature a bird that made its nest from mud – and phoebes do – thinking it'd be a nod to "banks" of a different (and better) sort: those of clay and sand. But then I found the Mary Oliver poem "Messenger" and thought this was a better invocation:

My work is loving the world.

Here the sunflowers, there the hummingbird—

equal seekers of sweetness.

Here the quickening yeast; there the blue plums.

Here the clam deep in the speckled sand.

Are my boots old? Is my coat torn?

Am I no longer young, and still half-perfect? Let me

keep my mind on what matters,

which is my work,

which is mostly standing still and learning to be

astonished.

The phoebe, the delphinium.

The sheep in the pasture, and the pasture.

Which is mostly rejoicing, since all the ingredients are here,

which is gratitude, to be given a mind and a heart

and these body-clothes,

a mouth with which to give shouts of joy

to the moth and the wren, to the sleepy dug-up clam,

telling them all, over and over, how it is

that we live forever.

Thanks for reading Second Breakfast. Please consider becoming a paid subscriber, as your financial support enables me to do this work. (But a fair warning: I plan on taking some time off in November and December. So if you need to see proof of what you pay for in in your inbox each week, maybe wait for the new year to start a paid subscription.)