No Future in Our Dreaming

It's been another very dark week, hasn't it. Not even Cory Booker's act of elocutionary endurance could shake me out of the gloom.

It's a personal gloom, no doubt – this week marked the five year anniversary of the last time I saw Isaiah. It was early in the pandemic, the first week or so of "social distancing." So we didn't even hug goodbye.

It's hard to shake that feeling of being unmoored when the future you imagined yourself, your children is ripped away. Trump has already done that once to that country. Even though I suffered the most unimaginable loss during his first presidency, there are ways in which this time around, it almost feels worse. Or at least, it's one thing to be stoic and resilient about your own grief and loss; it's something else to witness the destruction of democracy.

And it's something else to see so much complacency, so much complicity, to see smart people embrace the notion that we're going to AI our way out of this mess.

The Washington Post's Philip Bump asked a number of political scientists and historians what America might look like a decade from now. Placing today's political events on longer time frame is imperative for any discussions we might have about education, of course. Because, despite all the talk about speed and efficiency by ed-tech entrepreneurs, students will spend years and years and years in school. The decisions that the Trump Administration makes now – defunding scientific research and higher education, for example, and dismantling civil rights protections – will have long term consequences for even the youngest of today's students, for their future, for the future of civil society.

The respondents in Bump's informal survey all posit a decline in democracy and a rise in authoritarianism, no surprise, with Georgetown University's Thomas Zimmer specifically pointing to the "tech right fever dream of anarcho-capitalist feudalism" and the role it might play in shaping American autocracy.

The "tech right fever dream of anarcho-capitalist feudalism" is inseparable from artificial intelligence. To embrace AI is eschatological: to surrender to a promise of algorithmic assurances, to fuel a techno-imperialist information utopia, to engineer a post-human paradise, and – this one is within reach, to be sure – to automate democracy's undoing.

Education journalist Jennifer Berkshire urges us to do better at "connecting the dots." "I often have the feeling when reading the journalists who cover education that they’re reporting from inside a paper bag," she writes. "In other words, it’s impossible to make sense of the ‘why’ of what’s happening if you’re not listening to the larger stories that Trump et al are telling about the world they want to recreate."

We might wonder, for example, why on earth Trump would shutter the Institute of Museum and Library Services, the largest source of federal funding for libraries. Its budget is pretty insubstantial after all – $290 million last year, money spent mostly on database systems and collections management. Of course, any supposed cost-savings for taxpayers isn't really the point of any of the DOGE endeavors. In this case, an attack on libraries is tied to the right-wing belief that libraries are "woke" – the incredible danger posed by Drag Queen Story Hour. Trump supporters are clearly committed to censorship and are actively engaged in book-banning initiatives. But libraries are more than books. They have also become a key "safety net" in many communities, where the poor and homeless can access social services. So that too is a reason they must go.

Dismantling the nation's library and museum system – "restoring truth and sanity to American history" as Trump's recent Executive Order put it – is a demand for ideological compliance, to be sure, an attempt to diminish our ability to think and read and write and critique and learn. Connect the dots, as Berkshire urges us, to the privatization of information and educational resources, to technological solutionism, to the capacity for an algorithmic, centralized control of content.

The attack on higher education is an attempt to shape ideology too. But it also underscores the right-wing's belief that the "wrong people" are getting college degrees – Black people, Brown people, immigrants, women. As Berkshire argues, the latter is particularly central to white supremacist and eugenicist concerns about "shrinking birth rates," something Elon Musk frequently whines about. The Heritage Foundation, for its part, has suggested that changes to education policy might increase the "married birth rate," arguing that "Expensive and misguided government interventions in education are, whether intended or not, pushing young people away from getting married and starting families—to the long-term detriment of American society.” These "government interventions" include things like financial aid, BA requirements for teachers, and subsidized childcare programs – now being eradicated at the federal and state level – that, as they see it, lure women into college and then into the workforce and away from the maternity ward.

(Related, in Wired: "Far-Right Influencers Are Hosting a $10K-per-Person Matchmaking Weekend to Repopulate the Earth")

The privatization of public education – both K-12 and higher education – has long been the goal of neoliberal reformers and philanthropists, and technology companies have been happy to help. Indeed, many of the core capacities of these institutions have already been outsourced – course management, registration, communications, online offerings, and so on. Deals with AI companies – more on that below – can now fulfill the long-promised automation of instruction as well.

The Trump Administration's policies in and around and beyond education, as Berkshire points out, are explicitly pro-management and anti-labor – the elimination of collective bargaining rights of federal workers echoes the elimination of these rights in red states. It's a "bosses on top" mentality, as John Ganz has described it, which insists that “the authority and power of certain people is the natural order, unquestionable, good.” Efforts to undo DEI are not simply attacks on the diversity of the workforce, they're an attack on civil rights and labor rights broadly held. And efforts to undermine public education aren't simply an attack on teachers' rights as workers, but on children's rights not to work – as legislators in Florida, for example, are seeking to end child labor protections.

AI is all part of these strategies of displacement and control.

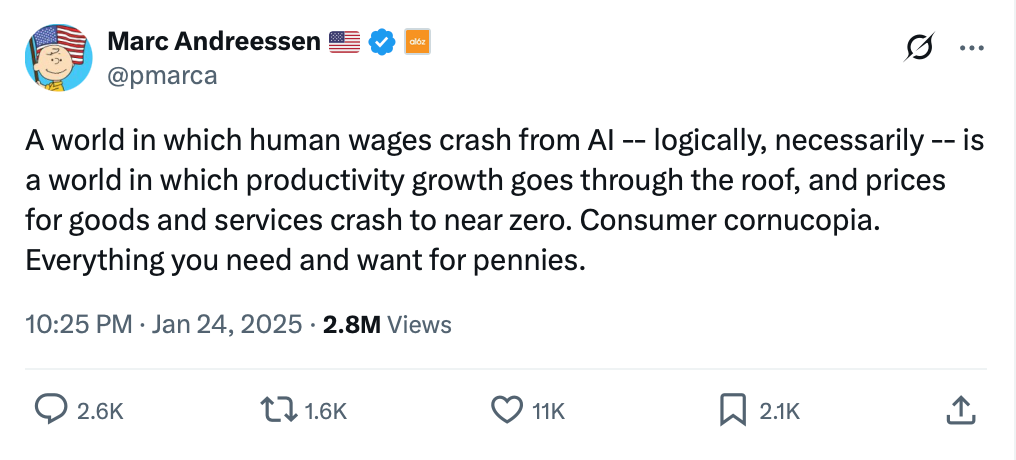

It's impossible not to read the threat of AI as a threat against workers, a threat that cannot be disentangled from either Trump's explicit executive orders or the generalized anti-union stance of Silicon Valley.

(It's worth remembering too: it's never simply a question of what computers can and cannot do, but about whose interests computers are built to serve. That is to say, robots are not going to take away your job; your boss is.)

Among those whose interests are best served by this push for artificial intelligence, other than "your boss": the fossil fuel industry. According to The Guardian, the industry (one of the main backers of right-wing think tanks, it's worth noting) is thrilled with this turn of events, as pressures to move to alternative energy sources have largely dissipated. The industry bankrolls oligarchs like Trump, and it's paying off. "Energy Transfer, the oil and gas transport company behind the Dakota Access pipeline, has received requests to power 70 new data centers," The Guardian reports, "a 75% rise since Trump took office."

We cannot simply put the environmental consequences of AI and big data to the side – this weird rhetorical move that I notice lots of people doing. We must – sorry to belabor Berkshire's point here – connect the dots: AI, the petroleum industry, Russia, misinformation, autocracy, war, the end of the world.

(Related: Amy Westervelt on "What the Technofascists and Religious Fanatics Have in Common: End Days Theology.")

OpenAI versus Anthropic. On one hand, this feels like the early 2010s, when school districts and colleges would compete with alternating press releases about who'd "gone Google" or who'd signed a contract with Microsoft for Outlook and Office "in the cloud." Or who'd renewed their LMS contract with Blackboard versus who tried to position themselves as a fellow "disruptive innovator" by going with the upstart Instructure. (The former example, to be fair, was about creating brand loyalty for life; the latter, about successfully creating generations of students that recognize ed-tech truly sucks.)

I reckon there's a case to be made that these decisions – the outsourcing of information infrastructure to big technology companies – simply weren't all that great for education, for maintaining a vision of academic computing distinct from the technology industry's desires (read: data), or for maintaining a mission focused on teaching and learning rather than a financialized mission where the priorities are capital.

But hey, past is prologue, so here schools are today, vying to boast their ties and tie their futures to AI. This week, Techcrunch reported that "Anthropic launches an AI chatbot plan for colleges and universities." It's integrated right into the LMS, apparently, which is to say it's compulsory which is to say fucked up. Anthropic hopes "to capitalize on the growing number of students using AI in their studies," the article tells us, and nothing says you are looking out for the best interest of your students like treating them – to invoke a little Mario Savio – like "raw materials."

There's been a huge narrative push recently to position Anthropic as the "good guy" in this whole fight, I've noticed. Something about OpenAI's Sam Altman standing too close to Trump, maybe. I don't know. But Wired's Steven Levy just published an article that uses the word "responsible" so many times to describe Anthropic you know it's overcompensating for something: "If Anthropic Succeeds, a Nation of Benevolent AI Geniuses Could Be Born."

To be clear, the "benevolence" here is tied to "effective altruism." Dario Amodei, its co-founder, has written extensively about his vision of a super-intelligent AI that will magically solve every global problem. Anthropic was first funded by fellow effective altruist Sam Bankman-Fried, the convicted crypto-fraudster who famously said "I don’t want to say no book is ever worth reading, but I actually do believe something pretty close to that. … If you wrote a book, you fucked up, and it should have been a six-paragraph blog post." So that bodes very very well for this model of AI and education. Congrats all 'round.

Incidentally, AI researchers Timnit Gebru and Émile Torres include effective altruism in their "TESCREAL bundle" of ideologies – the ideologies permeate AI discussions about AGI and that are not only inseparable from the ideas of early 20th century eugenicists, but that are deeply intertwined with an end-times worldview.

There is no future with AI.

Others' dots:

"The Hidden Curriculum of Generative AI" by Melissa Warr and Marie Heath. Among their findings: "feedback to Black and Hispanic students tended to be more authoritative in tone, echoing the power dynamics often found in schools. It’s relatively simple to not use GenAI tools for grading; but this initial result demonstrates that the very language LLMs use when personalizing responses may perpetuate inequities."

"How teachers are trying to outsmart AI" by Jamie Bartlett. "Any time saved through AI-generated lesson plans will be quickly gobbled up by watching people tediously type essays into Google docs. This is the iron rule of technology adoption, whether parking apps or hyper-intelligent machines. Despite its promise to make your life easier, it will simply create a series of new time-consuming problems for you to overcome."

Josh Brake with "thoughts on how to prevent AI from robbing you of the value of building expertise of your own." "Understanding how to do something without AI is one of the prerequisites for learning how to do it well with AI. Without that pre-existing expertise, how could you even know if the product is any good? Just trust the vibes? You're putting your faith in a tool that by design is chasing statistical likelihood instead of factual accuracy and has been trained to tell you you're right."

"Teaching AI Without Talking About Power Misses the Point," James O'Hagan argues. "It is not just about getting students to 'understand' AI. It is about recognizing that AI already understands them — because it has been trained to. And it is already being embedded in schools in ways that make understanding secondary to compliance."

"The Myth of a Safe Classroom" by Xian Franzinger Barrett. "After we study the ways that they can resist those who want to hurt them and their families, students often ask what we as teachers will do. 'We will do everything we can to prevent them from entering the building and to disrupt them to protect you from harm,' is what I say. We cannot ensure their safety, but we can promise that we will fight and that they will never be alone."

I would be remiss if I ended this too-long email without mentioning the passing of one of my favorite actors, Val Kilmer.

Most of the headlines about Kilmer's life and career refer to his roles in Batman or Tombstone or Top Gun. But my favorite will forever be the 1985 comedy Real Genius. There aren't a lot of "ed-tech" movies, mind you – The Matrix, Ender's Game, Class of 1999. So maybe I'm not saying much when I insist Real Genius is easily the best and the most important one.

In it, Kilmer plays Chris Knight, a smart-ass slacker of a student at Pacific Tech (a fictionalized Cal Tech), who takes his new, naive roommate Mitch under his wing. They and fellow "geniuses" have been recruited by Jerry Hathaway, a professor who unscrupulously uses their labor to develop military technology for the CIA. Assassination lasers, shot from space – it was the Eighties, what can I say.

The gender politics of the film are awful – there's only one female student, Jordan, and the only other women are groupies, of sorts. (Awful, but probably not far off from reality at CalTech's engineering program at the time where men outnumbered women 7 to 1, as Phyllis Rostykus, inspiration for Jordan, attests.)

Kilmer is absolutely magnetic as Chris – I mean, he was magnetic in everything – but it was always the character of Lazlo Hollyfield that gave me pause. Hollyfield, once a star pupil, had suffered a nervous breakdown when learning that the technology he'd helped design could be used to kill. He still resides in the tunnels beneath the university, emerging from time-to-time from the closet in Mitch and Chris's room. It's Lazlo who informs the students that the project they've just completed for Hathaway could easily become a weapon – there's a dawning recognition among the students of what they've done, prompting them to resist: to reengineer and retarget the tool to destroy Hathaway's home during his demo to the government (or specifically, to heat the home that's filled with popcorn kernals, turning it into a gigantic popcorn popper. You see, kids, microwave popcorn was a goddamn miracle back in the day).

Lazlo serves as the voice of techno-morality (although in the final scene, he pulls up in an RV he's won it by using math to rig the lottery – but, hey, at least he's "free"). And Real Genius reminds us that there are always ethical consequences to "innovation," that we are responsible for the tools we build whether or not we give any thought to how they might be utilized.

But I think there's another lesson too, particularly for education technology: that we are doubly responsible for tools we compel students to use and for the culture we build and use them in. Our tools shape us – cognitively and morally. Not every engineer professor is out there having their students design and develop weapons of war, obviously. (Although there are some who are absolutely doing this, including a community college in Texas that uses students to train military AI for drone missions. Phew. Bring back 80's Movie Night, Fayetteville Technical Community College! I dare you!) And when we compel students to use technologies that are intertwined with dishonesty, mistrust, exploitation, and war, we are not laying the foundation for a future that can be anything other than that: immoral, ignorant, destructive, empty.

Here's to the students who think and care. Here's to those who fight back, who retain their humanity and refuse the machine.

Thanks for reading Second Breakfast. Please consider becoming a paid subscriber. Your financial support enables me to do this work (and to do this work from home, I should add. I used to make money by traveling and speaking, but it's starting to feel too risky). There's more to be said about the ways in which the future is being stripped from all of us, but I'm deep in my feelings about this this week. So I'll just leave you here, with all good wishes for your weekend.