Hard Times

"'Now, what I want is, Facts. Teach these boys and girls nothing but Facts. Facts alone are wanted in life. Plant nothing else, and root out everything else. You can only form the minds of reasoning animals upon Facts: nothing else will ever be of any service to them. This is the principle on which I bring up my own children, and this is the principle on which I bring up these children. Stick to Facts, sir!'"

– the schoolmaster Thomas Gradgrind in Charles Dickens's Hard Times

Charles Dickens cleverly links the factory and the classroom in his novel Hard Times, highlighting the pressures of industrialization to standardize and control the body and the mind, to shape workers and students in service of facts and numbers and, of course, to the benefit of the wealthy. And while I do think there are substantive problems with that too-pat phrase "the factory model of education," Dickens wasn't wrong to observe that, even by the mid-nineteenth century, we were building a system – a school system and an economic system – that valued "facts" at the expense of imagination (and the novel argues, of morality). What we can measure, matters; what we can count, counts. "Go be somethingological," Mrs. Grandgrind admonishes her children – whatever that is, as long as it's reasoned.

Education is still largely seen as (even structured as) the transmission of facts and the assessment of factual knowledge. Of course, it's more than that – much more than that. I'm not sure anyone would agree with Thomas Gradgrind that "facts!" are a complete description of any educational endeavor. And yet there remains an obsession with measurement and with a certain kind of knowability – a desire that "AI" is ready to tap into, to automate; a promise of information/salvation that so many of its evangelists believe the technology already (or soon! soon!) can offer. Somethingological indeed.

Way back in 1984 (the very year Mark Zuckerberg was born, funnily enough), technology journalist Steven Levy argued that the personal computer was poised to reshape how we understand and model the world – "a spreadsheet way of knowledge," as he called it, was emerging from software like VisiCalc and Lotus 1-2-3. In the intervening decades, many of our knowledge practices have been enframed by these "productivity tools" – how we know, what we know, how we express knowledge has been circumscribed not just the frameworks of the spreadsheet but by – my god, this phrase – "word processing." And now, forty years after Levy's article first appeared, we can see in "AI" that "spreadsheet culture in overdrive," as Leif Weatherby puts it – words have been thoroughly processed, counted, tokenized. Now we're told that the future of "intelligence" – an "AI way of knowledge" – lies in the algorithmic re-arrangement of number-jumbo, the optimized extrusion of text and code.

"We are being trained, not explicitly, but implicitly, to treat words as units of utility," Carl Hendrick writes. "Optimised, shortened, and surfaced by platforms whose guiding logic is not comprehension, but click-through. In such an environment, the act of reading becomes flattened: stripped of its reciprocity, its effort, its deliberateness. But something essential is lost in that flattening."

Much of the internet wants us to dwell in shallow, curated versions of our own minds. By encouraging us to constantly turn inward through personalised algorithms, we are no longer invited to encounter authentic otherness, but to loop endlessly within the contours of what we already know, believe, and prefer. We become trapped in a hall of increasingly vacuous mirrors, fed content that flatters, not confronts, until thinking itself feels like friction.

Instead of words written and read by and for and with one another – cultivating and sometimes clashing our ideas, loves, lives together – we're encouraged to sit alone and click on the fake-friend-fact-factory.

A world at once so ripe for data extraction and so very very empty.

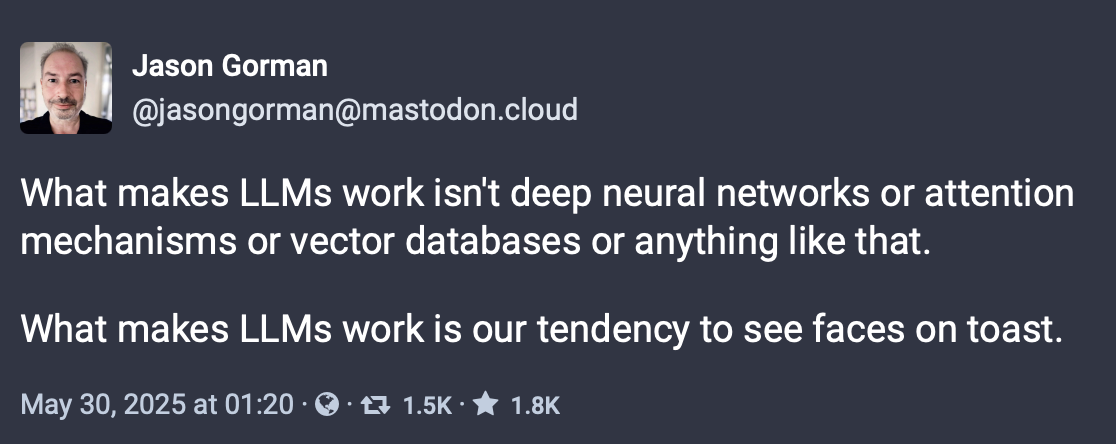

In their book The AI Con, Emily Bender and Alex Hanna use the metaphor of papier-mâché to describe LLMs. "When an artist uses materials with text on them to create a collage," Bender writes, "it's natural to assume that they chose the materials in part for the meaning of the text they include. Papier-mâché, on the other hand, uses paper (usually newsprint) simply for its physical properties. The text is incidental." To the "AI," there is no meaning in the strips of text it neatly pastes together; but wrapped around a balloon and hardened and painted, this mess of newsprint can take on a recognizable (although still hollow) form – and from there humans do see meaning.

I also very much like Bender and Hanna's phrase "text extruding machines," as it conjures images of "AI" as pink slime – not chicken, but not not-chicken, pink-slime makers assure us. I'm going to stop writing "generative AI" because I like the word "generative" too much to have it associated with McNuggets of textual slop. I'm also going to keep using "AI" instead of "artificial intelligence" and using those scare quotes, because 1) the phrase is used to paper over a lot of different technologies, 2) is still bound up in as much science fiction as it is real science, and 3) is not "intelligent," whatever the hell that means (derogatory).

Sold to us by conmen, "AI" remains a con. Case in point: Builder.ai, a company that just declared bankruptcy after being valued at over a billion dollars, was not in fact "AI" but 700 engineers in India pretending to be bots.

(Incidentally, I find it quite revealing those whose feathers get ruffled by Bender's more famous phrase "stochastic parrot" – that is, who are willing to think generously about allegedly smart machines but cannot seem to make the same gesture to a group of women scholars.)

Elsewhere in education / technology: No one knows how to deal with "student-on-student" child sexual abuse materials. Almost half of young people would prefer a world without internet, UK study finds. Judge rejects claim chatbots have free speech in suit over teen’s death. One in nine parents thinks their sports kid is going to "go pro" – precarity is making us all delulu. Google claims its "AI" model Gemini is "infused" with good "learning science" which – yikes. As Matthew Schmidt, Jason K. McDonald, and Stephanie Moore put it, "The research we don’t need will persist until we dismantle the systems that sustain it." So really it's no surprise, what with all this "AI" bullshit on top of the pre-existing ed-tech bullshit, that teachers are not OK.

Meanwhile in techno-fascism: Meta is working with weapons-maker Anduril (a company founded by Palmer Luckey, who sold his company Oculus to Facebook in 2014) to build military technology. Meta also inked a deal for nuclear powered data centers. The US is storing migrant children’s DNA in a criminal database. Silicon Valley wants to help me make a superbaby. Should I let it? Trump taps Palantir to compile data on Americans. (The head of Palantir in the UK is Louis Mosley, the grandson of arguably one of the most famous fascists in British history.) This is where the money and the power are right now: cop shit. And you are kidding yourself if you don't think that's what "AI" in education means. I mean, maybe it doesn't mean that for you personally, but show a little solidarity with those that it does, eh?

According to the research group AI Now in its new report on "artificial power," "The question we should be asking is not if ChatGPT is useful or not, but if OpenAI’s unaccountable power, linked to Microsoft’s monopoly and the business model of the tech economy, is good for society." It doesn't matter if "AI" "works" – if it makes things (in or out of the classroom) cheap, fast, easy, efficient, good. What matters is that it, what it controls.

Indeed, we are mistaken to focus on "AI" and its technological promises and not on how it functions as a set of political and economic practices, ones that consolidate power in the hands of a tiny number of companies – Amazon, Google, Microsoft, and Meta – and a small number of investors and entrepreneurs, many of whom have allied themselves explicitly with techno-fascism and with a vision of endless imperialism.

Education – and broadly all "information" and "knowledge" industries – is a soft target for them, I suppose, weakened by austerity, precarity; but in the end, technology oligarchs want to control the infrastructure of all aspects of all of our lives – the data, the computer processing, the networks, the software, the storage, the algorithms. And not even really for some profound philosophical reasons (although I'll have some more to say on that and Adam Becker's excellent More Everything Forever in Monday's newsletter); but simply for money and power.

Over the years, I’ve found only one metaphor that encapsulates the nature of what these AI power players are: empires. During the long era of European colonialism, empires seized and extracted resources that were not their own and exploited the labor of the people they subjugated to mine, cultivate, and refine those resources for the empires’ enrichment. They projected racist, dehumanizing ideas of their own superiority and modernity to justify—and even entice the conquered into accepting—the invasion of sovereignty, the theft, and the subjugation. They justified their quest for power by the need to compete with other empires: In an arms race, all bets are off. All this ultimately served to entrench each empire’s power and to drive its expansion and progress. In the simplest terms, empires amassed extraordinary riches across space and time, through imposing a colonial world order, at great expense to everyone else.

The empires of AI are not engaged in the same overt violence and brutality that marked this history. But they, too, seize and extract precious resources to feed their vision of artificial intelligence: the work of artists and writers; the data of countless individuals posting about their experiences and observations online; the land, energy, and water required to house and run massive data centers and supercomputers. So too do the new empires exploit the labor of people globally to clean, tabulate, and prepare that data for spinning into lucrative AI technologies. They project tantalizing ideas of modernity and posture aggressively about the need to defeat other empires to provide cover for, and to fuel, invasions of privacy, theft, and the cataclysmic automation of large swaths of meaningful economic opportunities.

From Karen Hao's The Empire of AI: Dreams and Nightmares in Sam Altman's OpenAI

"You don't know what hard times are, Daddy. Hard times are when textile workers around this country are out of work. They got four or five kids and can't pay their wages, can't buy their food.Hard times are when the auto workers are out of work and they tell them, go home. And hard times are when a man has worked at a job for 30 years, 30 years, and they give him a watch and kick him in the butt and say, hey, a computer took your place, Daddy. That's hard times. That's hard times."

– "The American Dream" Dusty Rhodes to Ric Flair, in what is arguably the greatest wrestling promo video ever shot, 1985

Beware the heel turn.

Thanks for reading Second Breakfast. Please consider becoming a paid subscriber. Your support allows me to do this work.

Next month, I'll be a speaker at the virtual Conference to Restore Humanity, organized by the Human Restoration Project, a great organization committed to resisting the practices of the Thomas Gradgrinds of the world. Join us at the event.