Oatmeal and the History of the Branded Breakfast

"Quaker Oats -- it's the right thing to do" -- Wilford Brimley

Is breakfast the most branded meal of the day? I suppose that all meals in late-stage capitalism are to a certain extent. But there's something about breakfast and advertising — the ads for Ovaltine and Lucky Charms and Pop Tarts and Jimmy Dean Sausage and Folgers Coffee and on and on and on and on. It's not just that breakfast as we know it today was an invention of the late nineteenth century wellness industry, one that had to be marketed to the masses who were more apt to eat eggs and corn-cakes than Corn Flakes. It's also that, due to the power of The Morning Routine, many of us will eat the same thing for breakfast day in and day out — so if you can convince a customer to buy your product, you have a good shot at getting some incredible brand loyalty for years and years and years.

When you walk down the cereal aisle in particular, you're bombarded with not simply an array of choices, but with all that brightly colored packaging — arguably the most aggressive marketing in the grocery store.

The first cereal company to leverage this was Quaker Oats, whose maker registered its trademark in 1877 shortly before going bankrupt. When Henry Crowell bought the mill in 1881, he acquired the technology to process oats so that they would cook more quickly than would the traditional cut. But more importantly he acquired the Quaker brand name.

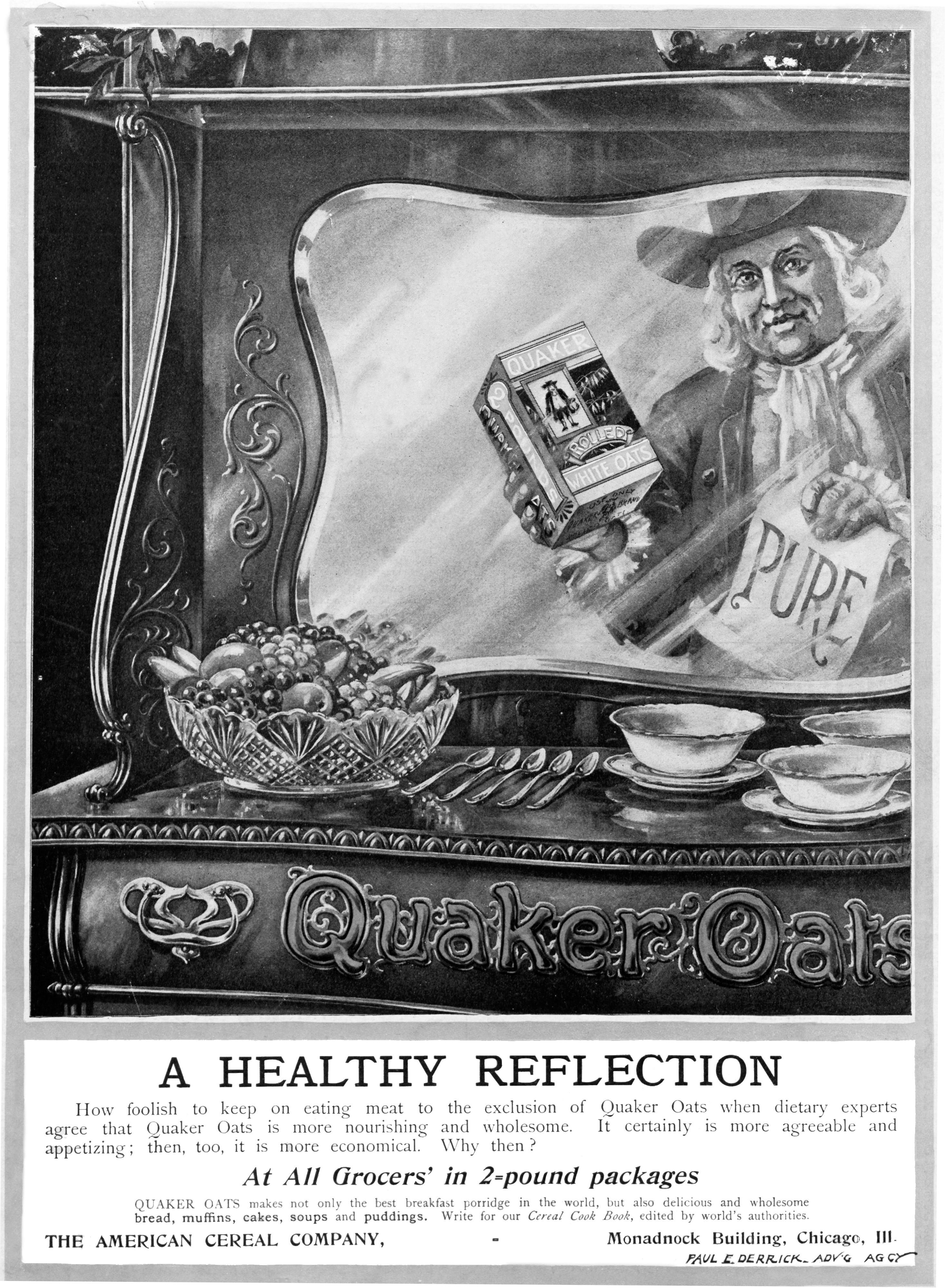

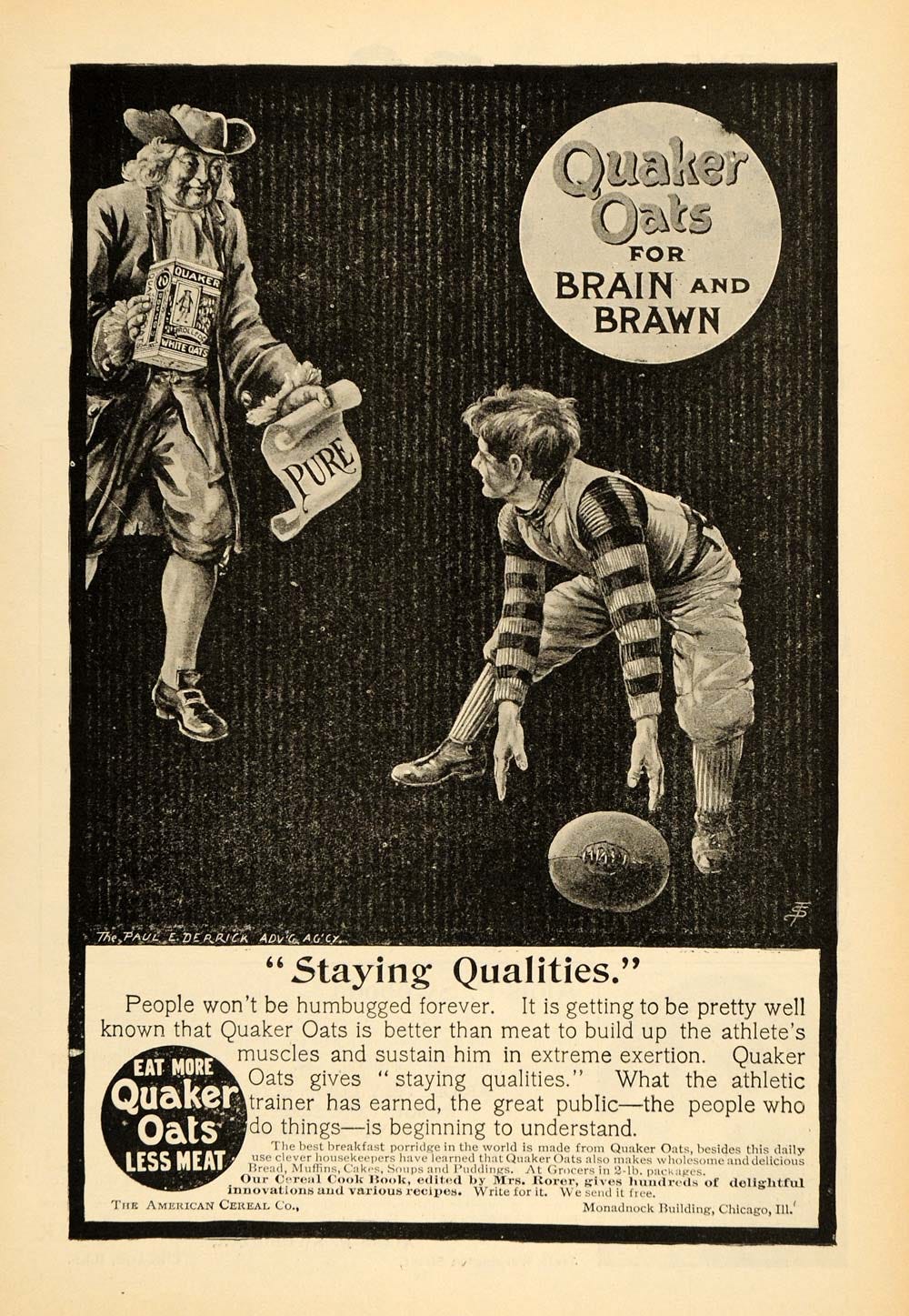

That name implied virtue and integrity. Part of the appeal of the Quaker Oats — which came packaged in a cardboard box, a relatively new technology itself — was that they'd be free from the contamination of the cereal typically purchased from bulk bins at the grocers. (The classic cardboard cylinder was introduced in 1915.) Indeed the Quaker was sometimes depicted holding a scroll that read "pure." But as Abigail Carroll argues in her history of American eating, the box wasn't simply practical; it was promotional. "Both the container and the image it bore set Crowell’s product apart, making it recognizable and trustworthy, and the public responded. In 1898, an article in The Living Age called Quaker Oats 'the form of porridge most in vogue.' Quaker Oats had become fashionable."

The discovery of vitamins in the early 20th century was also a boon to Quaker Oats, as oats are naturally high in B vitamins, something that the company was more than happy to highlight. (The company launched one of the first vitamin-fortified cereals, Sparkies, in 1940 — that "spark" was from thiamine. The brand was promoted by Little Orphan Annie.

(Terrible history of breakfast side note: In the late 1940s, Quaker Oats, along with MIT, carried out experiments on institutionalized children, feeding them "fortified" cereals to test the body's absorption of vitamins and minerals. The children, many of whom were mentally challenged, were told they were part of a science club; the iron and calcium in the cereal were radioactive so that scientists could trace them with a goddamn Geiger counter. "No harm was done," says MIT in typical MIT fashion.)

Quaker Oats was also one of the first cereal makers to offer "premiums" to customers who sent in money, along with a proof-of-purchase — the cut out "Quaker Man" trademark. Early giveaways included a double-broiler for making oats, a crystal radio set (built in the cereal’s cardboard cylinder), and — get this — deeds to tiny parcels of land — "oatmeal lots" in Milford, Connecticut.

In 1969, Quaker Oats acquired Fisher Price, lest you think that the marketing of breakfast is not deeply intertwined with the marketing of childhood. In 1971, the company helped finance the making of Willy Wonka and the Chocolate Factory, in exchange for licensing rights to branded candy bars. In 1982, it acquired US Games, a video game maker for the Atari 2600. (Rival General Mills owned Parker Brothers, which had seen great success with titles like Frogger.) In 2001, PepsiCo acquired Quaker Oats, not for the cereal, but for the sports drink Gatorade, which the cereal maker had itself acquired in 1983.

So much can be gleaned here about how a simple breakfast cereal shapes and reflects our cultural values about health, about efficiency, about science and technology, about food conglomerates, about advertising, about play — all from a little corporate history. And I haven’t even mentioned one of the greatest scenes in breakfast film history:

Yes, Mr T. Cereal was made by Quaker Oats — and is (was) just one part of a healthy breakfast.