Sputnik Deja Vu

I gave this presentation on Monday afternoon at Yale University. The talk was co-sponsored by the Department of Political Science, DOWN Magazine, the Education Studies Program, and The Politic. A huge thank-you to Jennifer Berkshire for inviting me and having me speak to her students.

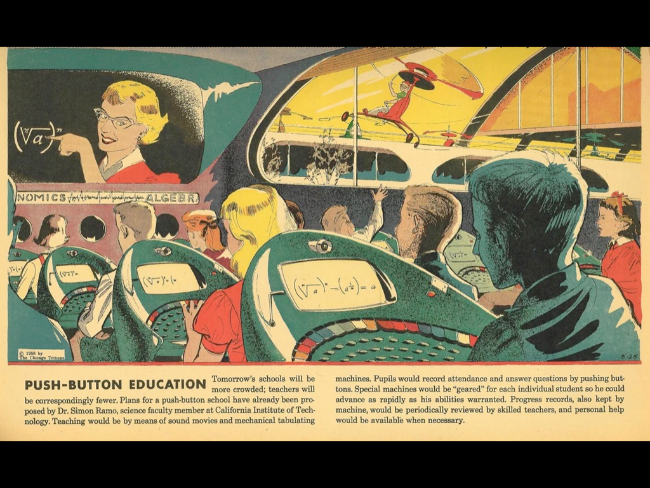

This is the May 1958 edition of Arthur Radebaugh’s Sunday comic Closer Than We Think: "Push Button Education." This was the future of education imagined by Cold War America; incredibly, it remains the future of education today. And that is my thesis this afternoon: that we are stuck in the past, with a vision of the future that is now some seventy years old. Despite being told over and over, that things are changing faster than they've ever changed before, that this moment and its technologies, are unprecedented, we are trapped in the Cold War imaginary – and importantly, an imaginary that might seem shiny and chrome, but upon closer analysis is steeped in fear and control.

Arthur Radebaugh was a futurist and artist, who, before his Closer Than We Think series, produced commercial illustrations for United Airlines, Dodge, Motor magazine, Burlington Railroad, the US Army, and others. I've argued previously that, contrary to computer scientist Alan Kay's famous saying that "the best way to predict the future is to build it," I believe "the best way to predict the future is to issue a press release." We can view Radebaugh's work as aspirational -- what he thought the future might be like based on scientific research at the time. But we should see it too as advertising: selling a vision that is deeply intertwined with commercial product development, not simply the advancement of science.

Closer Than We Think first appeared in 1958, was syndicated by the Chicago Tribune newspaper, and ran until 1963, reaching about 19 million readers at its peak.

Newspapers, for those of you too young to remember -- bless your hearts -- used to be printed on paper and delivered to your home or purchased at a “newsstand” on the way to work. Monday through Saturday, papers were black and white, but on Sunday, ahhhh Sunday, the paper was bigger, fatter -- full of colorful advertising inserts -- and most importantly, for kids and adults alike, had an entire section devoted to comics. Closer Than We Think was a one-panel comic that depicted the future, a future based in speculation and imagination, to be sure, but also pointedly referencing scientific research -- commercial and academic -- with a little text box, as we see here.

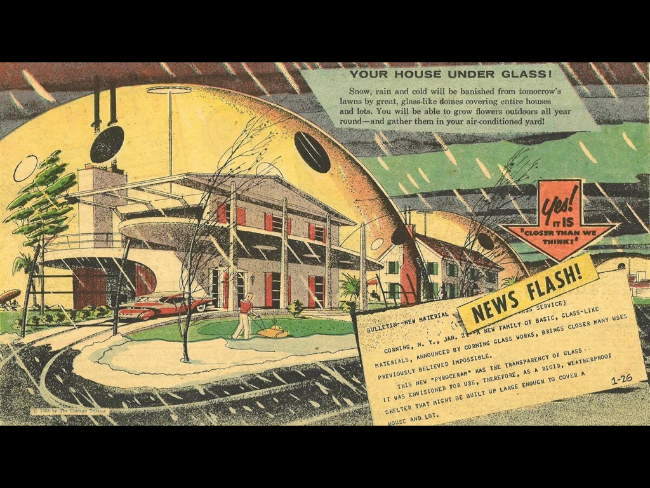

Topics of Radebaugh's Sunday comics included: "hospitals in the sky," "robot warehouses," "robot housemaids," "electric cars," "flying fire engines," "honeymoons on the Moon," "wall to wall televisions," and "orbiting space arks."

Radebaugh's drawings depicted a world that has been liberated -- a liberation, no doubt, that many people at the time were ready for, one they felt had happened or was in the process of happening; that is to say, a world that, if nothing else, was (supposedly) done with, liberated from the violence and destruction and sacrifice of two successive world wars. These illustrations depicted a future that promised to be better and -- this is crucial -- a future that would be technological, that would be affluent. (And as the Civil Rights Movement in the US and anti-colonial efforts globally were progressing in this same time period, I do feel the need to point out: a future that was white.)

Some of Radebaugh's drawings now appear to be quite prescient, some might say; the comic depicts technologies that have emerged (or that, maybe more accurately, seem closer today than in the 1950s and 1960s). We like predictions, we yearn for predictions (and we always have paid fortune tellers) as they give us comfort and reassurance in the face of uncertainty. But prediction became "big business" after World War II, particularly with the rise of computing; and science fiction became a significant cultural touchstone.

But I'd argue that we shouldn't really assess Radebaugh's work simply in terms of the accuracy of his predictions. Nor should we think that the gadgets that Radebaugh drew were (or will be) inevitable -- that he predicted the future. Radebaugh didn't have any special insight or foresight into the direction of science or technology. His illustrations -- and I think we can say the same about other depictions of the future, including science fiction -- were not about the future as much as they were a reflection of the moment in which they were created. They say little about "the future," and everything about Cold War America. The comics might be selling a certain future (and Radebaugh was, as I've said, very interested in product development), and they certainly sought to orient readers in a certain direction. But the future-imaginary is always about the present -- about the beliefs and values (not really even the science) of the moment in which they're drawn or written.

(So to return to my thesis: what might it mean that our depictions of the future of education now are the same as depictions of the future from the 1950s?)