Swords into Plowshares

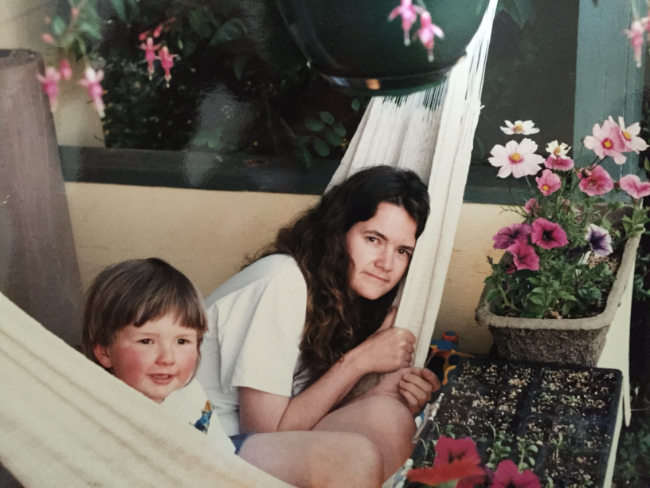

Yesterday marked my fifth Mother's Day without him. Tomorrow is the fifth anniversary of his passing. My beautiful boy, for whom I still grieve and will grieve every day forever; and despite his death, why I still fight.

When I was a sophomore in college (about a year before I got pregnant), I took a class on the history of non-violence, taught by the university's chaplain, Chester Wickwire. We read essays by Henry David Thoreau, Martin Luther King Jr, and Leo Tolstoy. We talked about imperialism and war, about community resistance and civil disobedience – in theory and in practice. We talked about faith and witnessing, about acts of courage, about good words and good deeds and, to borrow from the Serenity Prayer, "the wisdom to know the difference."

To say that this class changed my life feels a bit cliche, but it's true. It moved me in the moment – in that stereotypical way, I suppose, that some people have always wrung their hands at college students' political awakenings; and its influence on my thinking continues. Elements of what I learned there – those things both explicitly laid out on the syllabus and the class's implicit teachings that have taken years to bloom – run throughout all my work; they were there long before I started writing about education technology. My masters thesis and my unfinished dissertation both examined radical street theater and political protest, for example. But there are other traces: a commitment to community literacy; a belief in the transformative power of education, not for personal skill development but for social liberation; a sense of responsibility for creating a better world. I sometimes think of my writing too, I confess, more as sermon than scholarship.

Among the guest speakers in that class was the peace activist Father Phil Berrigan, who I remember as being very tall – that's probably my mind granting appropriate stature to this giant of pacifism. He spoke of his long and fervent opposition to war. He described the actions that he and a handful of others had undertaken to draw attention to the anti-Vietnam and later the anti-nuclear movements. He told us how, at first, they poured a red liquid mixed with their own blood over draft cards to destroy them, how they later bled and hammered on missile-carriers as they prayed.

Berrigan was part of several groups whose names came from their collective criminal trials: the Baltimore Four, the Catonsville Nine, the Harrisburg Seven, The Plowshares Eight. But he is best known for the latter and for the Plowshares Movement more generally, particularly the protest staged in 1980 at a GE plant where Minuteman missiles were manufactured. Berrigan, his brother, and six others were arrested and charged with multiple felonies and misdemeanors. He spent many many years of his life in prison for this and other acts of civil disobedience. He'd been paroled shortly before he came to our class in 1991, only to be sentenced again in 1999 after another protest.

Berrigan's group, the Plowshares, took its name from a passage from the Book of Isaiah: "and they shall beat their swords into plowshares, and their spears into pruning hooks: nation shall not lift up sword against nation, neither shall they learn war any more."

A couple of years later, I named my newborn Isaiah Tolstoy – all my fierce hope for a world transformed, for peace and justice and liberation.

Isaiah is gone – Father Phil and Chet too – and for a time, my hope was as well. (Here's where I turn to Gramsci, I'd say, more than God to remind me of optimism and will...)

Computing is a weapon of war. It is a sword, not a plowshare, despite all the rhetorical twists and turns we might try to make it so -- "a bicycle for the mind" and whatnot.

Computing was born in war, in the code-breaking work at Bletchley Park during World War II (or arguably, even earlier in the imperialist and industrialist expansion that Charles Babbage hoped his calculating machinery would help automate). During the second half of the twentieth century, massive amounts of military funding poured into science and technology research in the name of national security and national defense -- money that, to be clear, poured into universities, whose post-war "golden era" exists thanks to this military-industrial complex, to the influx of dollars and young white men whose college education was subsidized by the GI Bill.

The computer. The Internet. Artificial intelligence. These are military technologies, first and foremost. First and foremost and for a while now. And while certainly we must resist the teleology that positions these technologies always and forever thus, we have accomplished little, I'd argue, in wresting them free from their origins in "command control communication intelligence," from that cybernetic move to reduce everyone and everything to code.

"Feminist cyborg stories have the task of recoding communication and intelligence to subvert command and control," Donna Haraway wrote in her "Cyborg Manifesto" over forty years ago. This is still, without a doubt, the task ahead, not behind us.

In his book The Children's Machine, Seymour Papert observed that "The people who forge new technological ideas do not make them for children. They often make them for war...." He argued that his programming language "Logo was fueled from the beginning by a Robin Hood vision of stealing programming from the technologically privileged (what I would in those early days in the 1960s have called the military-industrial complex) and giving it to the children."

While I appreciate the act of subversion, this theft was a reallocation of technology, not a repudiation of its underlying origins or epistemology.

Indeed, Papert praised the cyberneticians and their military mathematics for developing new objects and a new way of thinking about old ways of defeating enemies. Norbert Werner had imagined a "smart missile" designed "to perform in the end even better than the traditional weapon." Turtle programming, Papert argued, would help children build this same sort of "managed vagueness" in a cognitive and material feedback mechanism.

"It's a metaphor," one might retort. And it is. And it isn't.

Education technology has been part of what historian Douglas Noble called "the classroom arsenal." Even before the advent of computing, much of the development of educational technology was undertaken by military researchers (particularly at the Office of Naval Research and Air Force Office of Scientific Research) – from the Army Alpha and the implementation of standardized IQ testing to early teaching machines, designed to automate the training of recruits. Indeed, B. F. Skinner observed, in an address to the Aerospace Education Foundation of the Air Force in 1968, that "educational technology has developed rapidly in the [Armed] Services and it is moving into the schools."

A decade earlier, Simon Ramo, an instructional technologist as well as "the father of the intercontinental ballistic missile," had penned an essay titled "A New Technique in Education" that imagined a future of a push-button classroom of personalized learning – a future that I argue in Teaching Machines introduced the automation of education to a much broader swath of the American public than did Skinner's academic writing (or the dismal sales of his teaching machines). This is a future that continues to resonate with today's ed-tech evangelists.

And yet, I'm still a bit taken aback when I hear someone like Salman Khan invoke Ender's Game as inspiration for Khan Academy and now for his AI chatbot Khanmigo – even though he's acknowledged the book's influence on his thinking over and over again. Ender's Game is a novel in which children, without their knowledge or consent, are recruited to fight a war to exterminate an alien species. They are taught via military AI; they become weaponized themselves.

“I am making a way in the wilderness. and streams in the wasteland."

We're still eating the leftovers of World War II, environmental activist Vandana Shiva has repeatedly argued, reminding us how munitions plants switched from making explosives to making fertilizer and pesticides, how industrial-scale warfare turned to industrial-scale food production.

Arguably we're still being fed via the information machinery of the war and the Cold War too.

How does this diet of weaponry shape who we have become? What does it mean to base our imagination of some sort of extended cognitive capacity on the machines and systems bound up in national defense, in a Red Scare so fevered that Nazis remained welcome and supported in the scientific community as long as they could help us win the Space Race? If nothing else, it seems, it has helped create a technology industry in which there has been no real reckoning for its role in violence, imperialism, surveillance, eugenics, environmental and genocidal destruction.

Computing remains a weapon, despite the clever stories we tell ourselves that make us feel less complicit in its violence – violence to one another, to the planet, to ourselves, to other ways of knowing.

To turn this sword into a plowshare requires a much greater shift (one I'm not even sure is possible) – not without a much broader shift in power, without a shift in economics, to be sure, without a shift in how we think and care. And AI – this idea bound up in the military intelligence – shifts us in the opposite direction, towards an automated thoughtlessness, algorithmic indignity, into a future run by those with no humility and no remorse.

To turn the sword of computing into a plowshare requires a much greater sacrifice than many seem willing to make, as caught up as so many people are, so many decades later, in the cybernetic fictions and Cold War era fantasies of thinking machines – fantasies of the very men who built the bomb.

To turn the sword into a plowshare must be an endeavor that enables, embraces life – all life.

It does feel hopeless sometimes. This week – Mothers Day and death day – forever more for me, I guess, the darkest. I grieve, I grieve, I grieve.

And then I pick myself up, and I fight.

Thanks for reading Second Breakfast. I'm going to be taking the next week off from the newsletter to spend time deep in my feelings.