Teaching Machines (for Bodies, Not Brains)

Many histories of education technology start with the hornbook, a fifteenth century invention that, according to Bill Ferster, "married pedagogy and content knowledge into a physical device" — a device that allowed students to learn their letters (without tearing up or writing in an actual book, I guess).

Of course, where you begin the history of education technology reveals much about how you see the field today – as something that "marries pedagogy and content knowledge into a physical device," most obviously. (Or as something that you yourself invented because you never bothered to read a single book on the history of education but still managed to capture the attention of a bunch of Silicon Valley investors and philanthropists, but I digress.) How you tell the story of ed-tech's past reinforces what you imagine the practice of teaching looks like — then, now, and in the future — as well as what you see as "the subject" being taught.

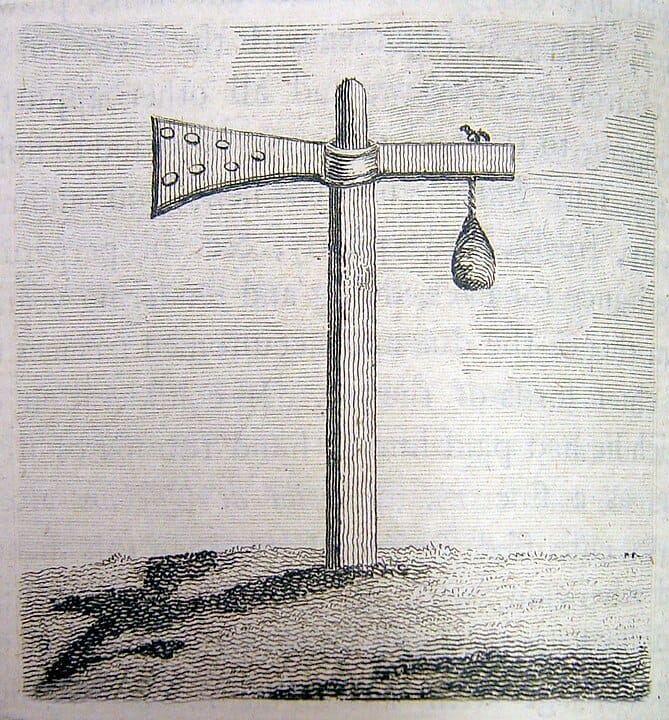

History is full of physical devices used to teach and to learn; but often what they taught wasn't "content knowledge" — at least what we classify as such today. Take the quintain, for example, which was used for hundreds of years (probably predating the hornbook) to teach jousting.

And to teach both riders and horses.

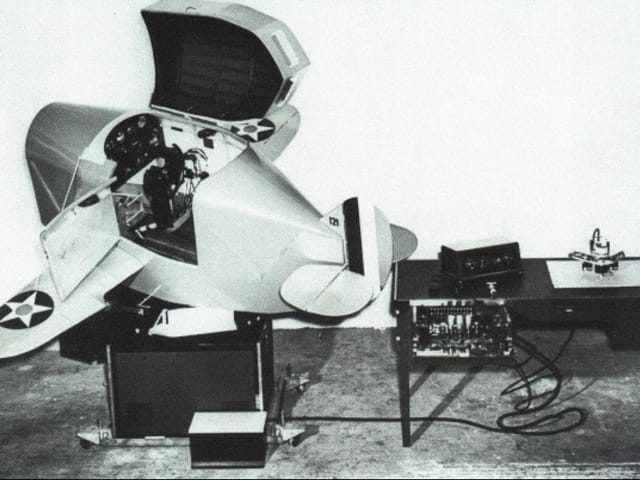

Skinner's work with pigeons aside, ed-tech doesn't much care to highlight its history as one grounded in the training of animals. Nor does it like to dwell on the important contributions that the military has made to the field — the quintain, the blackboard, the flight simulator, the learning object, the Internet. And there's very little in histories of ed-tech about the body. As in: next to nothing.

Education technology tends to dismiss embodiment. Even when folks tout "learning by doing," it's often reduced nowadays to "learning by clicking." You'd think that having just lived through several years of Zoom school, we'd be more willing to prioritize the importance of teaching and learning with our bodies in physical spaces with other bodies. (Or even have more nuanced conversations about the effect on bodies of teaching and learning in digital and non-digital spaces.) Alas.

It's not just ed-tech, of course. This is a broader cultural shift, one that is hardly new. From N. Katherine Hayles in How We Became Posthuman (which is 25 years old now, holy crap):

one could argue that the erasure of embodiment is a feature common to both the liberal humanist subject and the cybernetic posthuman. Identified with the rational mind, the liberal subject possessed a body but was not usually represented as being a body. Only because the body is not identified with the self is it possible to claim for the liberal subject its notorious universality, a claim that depends on erasing markers of bodily difference, including sex, race, and ethnicity.

As I noted in my rambling thoughts in Monday's newsletter on the Olympics and AI, I think there's something about this erasure of embodiment that's crucial to our understanding of ed-tech, sure, but also more broadly of artificial intelligence — it's both an erasure of difference of bodies and a re-inscription of the hierarchies surrounding "brains" (which of course is inseparable from social hierarchies surrounding bodies).

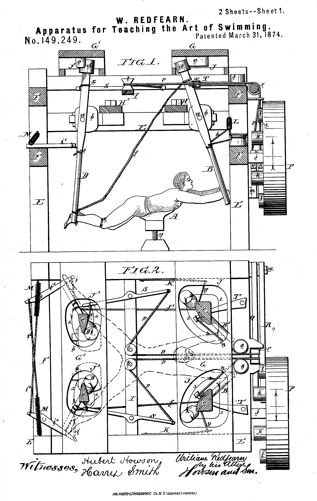

I'm not sure what the study of the history of teaching machines designed to train the body can help us see – but I'm curious nonetheless. Like this nineteenth century machine, for example, designed to teach swimming without ever having the student enter the water. Something about control, certainly. Something about safety, maybe. Something about our long-running belief that everything is an engineering problem and that we can craft bodies and brains to that end.

Thanks for subscribing to Second Breakfast. A lot of emails from me this week, I realize. It won't happen again for a while. I promise. But it's thanks to your support of this newsletter that I'm even trying to sort through some of these ideas about bodies and minds and teaching machines.