The Bay Bridge Half Marathon / The Wellness Trap

A race report disguised as a book review; a book review disguised as a race report; a series of questions that fundamentally challenge my work...

Second Breakfast doesn't officially launch until June, but I'm getting into the rhythm of writing and sending newsletters. This is the type essay that you'll sometimes get as a subscriber — in this case, a blend of book review and self-reflection.

Here's one of the sentences from Christy Harrison's new book The Wellness Trap that I've been sitting with since I finished reading it:

While for some people a fixation on wellness starts precisely because they’re having health problems, in hindsight I can see that for me it was the pursuit of wellness itself that triggered at least some of my conditions.

Over the past few years, I have also been "pursing wellness" — I'd be more likely to use the word "fitness," I reckon, but as Harrison makes clear, wellness culture, fitness culture, and diet culture overlap to such an extent that it's almost impossible to tease these apart.

I didn't start this pursuit in order to address a health issue, even though I was, I soon realized, dealing with such: in the summer of 2020, I was diagnosed with a heart murmur; this was traced to severe anemia; after months of testing, this was eventually linked to massive fibroids on the exterior of my uterus that had me bleeding so heavily for weeks out of the month that I could hardly leave the house. I was lucky, I suppose: conventional medicine did find what was wrong; and conventional medicine did address the problem — via iron supplements, blood transfusions, experimental medication, and eventually a uterine ablation.

But if my "pursuit of wellness" — my "fitness journey," god, I hate that phrase — wasn't aimed initially at addressing these medical issues, it was certainly bound up in the mental health struggles I was facing around that same time (and that I will deal with for the rest of my life): that is, trying to live in the midst of the pandemic and, of course, trying to live after the loss of my son.

I was devastated; I was broken; I wanted to be, I needed to be strong.

What I can see now too is that I desperately needed to have, wanted to have control over a life that had veered so wildly out of control — my life, obviously, but also the life of my kid. A few months after Isaiah died, I stopped drinking. I started working out more — I'd started doing yoga in the early days of the pandemic, but when I turned 50 I started powerlifting and then about a year-and-a-half ago, took up running.

I fell easily into training — it was a relief to hand over the thinking and planning to coaches and instructors who told me what to do with my body. I just had to show up and go through the motions.

I was (am) shattered; I was (am) also, ironically, the strongest I've ever been in my life.

But "the pursuit of wellness" isn't entirely positive, I can see, as it demands in ways both subtle and overt that one bends one's body to the values of individualism, capitalism, productivity, efficiency, and surveillance. And, of course, thinness and whiteness. "Wellness" is a technology — to borrow from the physicist Ursula Franklin: it's not just a collection of gadgets and artifacts; it's a practice, a mindset, an ideology.

Despite being labeled a "luddite," I have always been deeply curious about gadgets and their histories. Although I've left ed-tech — phew! — that technology critic in me remains interested in the kinds of stories we're told about how new technologies will improve our health and, for both professional and amateur athletes, boost our "performance." Having written a book on the influence of B. F. Skinner on the development of ed-tech, I was hardly surprised that this new topic I’d stumbled into — the topic of Second Breakfast, i.e. the technologies of food and fitness — was also deeply influenced by behaviorism. (And, no doubt, by Taylorism as well.) Even the language echoes Skinner's work: "training," "conditioning," and so on.

Before this "pursuit of wellness," I'd never really dieted before. (Thank you, genetics.) I'd never really "watched what I ate" or cared all that much about my physical appearance (except during junior high and high school — ugggggh). But I started tracking my macros, as that's what the Internet says to do to make sure I was getting enough protein. I bought a scale for the first time in my adult life; I started weighing myself daily. I already owned an Apple Watch, and it was designed to monitor my activity, to encourage me to "close my rings." I tracked my food, my water, my steps, my walks, my lifts, my runs using a variety of apps and spreadsheets.

I have found immense mental strength in my newfound physical strength and visa versa. But all the monitoring and tracking are perfectly poised to unravel all that. And I've often wondered at when one crosses the line between wellness and malady. Is there such a thing as "just a little bit disordered" in one's relationship to food or exercise?! I mean, I've never been athletic ever in my life, and now that I'm fifty-something, I'm thinking of running a marathon. That's fucked up, right?

I ran my second ever half marathon on Sunday. My first was just six weeks ago, and the decision to do two races back-to-back like this seemed a questionable one. I didn't know how well my my body would handle *one* event like this. I hit my goal that first time around — I ran 13.1 miles in under 2 hours — so I told myself that I needn't fret about my performance — "just have fun." (I'm running 13.1 miles. Am I having fun? Yes?! What is wrong with me?!)

That said, the past six weeks of training in between races were great; I am, dare I say, "conditioned." I've felt stronger in my weightlifting sessions — it's been challenging to be a "multi-sport athlete" and do both, particularly as I ramped up the running miles for my first half marathon. All of my runs went pretty well, particularly now that I am finally learning how to run more slowly, how to stay in "Zone 2" — another one of these technological mandates that I'll write about more in a subsequent essay here in this newsletter.

So, I lined up on Sunday morning, hoping to at least match the outcome my previous half.

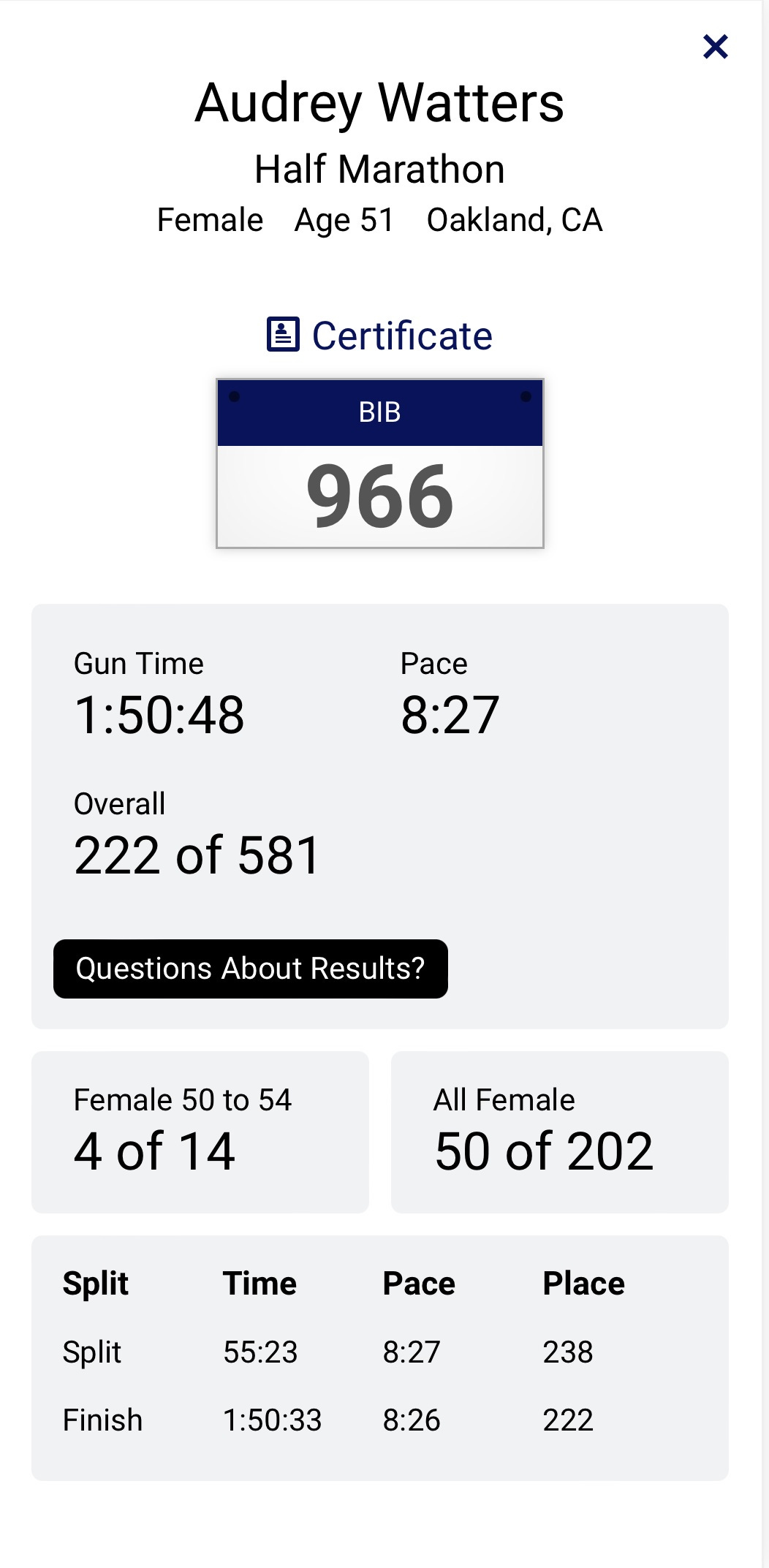

Friends,I beat it by almost four minutes — eons, really, in runner's time.

But the course — an out-and-back through West Oakland and across the Bay Bridge to Treasure Island and back — was short. When I crossed the finish line, my Garmin — and yes, I've switched to Garmin now that I'm a runner, and yes, I have another essay in the works on fitness technology and identity — had me at mile 13. I trotted around the finish line area for a few yards, but pressed "stop" on the watch before I hit the requisite 13.1. And so neither my watch nor Strava recorded that I ran a half marathon. My race didn't "count."

I count it. Of course I count it. The race officials count it. The chip on my bib counted it. And even if the race was .1 mile short, I'll count it as a PR. 1:50 and change. Fuck yeah.

That said, I am kicking myself for stopping my watch too soon, because there's something about that tracking technology that is so powerful in its validation — or in this case, invalidation of our fitness and health. And somehow this is my fault — my "user error" with the technology — and not the fault of the race organizers, the people who's job it actually was to make sure the half marathon course was a half marathon in length.

This race was harder, and not just because of the slight incline as one ran along the Bay Bridge. I ran faster — somewhat worried that I was going at a pace I'd be unable to sustain for 13.1 miles but knowing I could probably push myself harder: I'd left some "fuel in the tank" in my previous half marathon. I ate two gels — and yet another essay is forthcoming about the technology of "fuel" for athletes and the problems with labeling food as fuel; I'd eaten three in my previous race. I don't think the lack of carbs were the problem however; I think I was dehydrated. It was warmer than I expected. There weren't enough water stations, and at the few there were, the water was in plastic cups. I'd mastered the trick of the paper cups — drinking and running is tricky! You pour out most of it, fold the edges shut and sip a little before tossing the rest aside. Plastic cups don't fold — lousy, lousy technology. I tried to gulp and spilled most of the liquid down my chest. It's not so bad to be covered in water; but at one hydration station, because someone handed me electrolytes, I found myself covered in stickiness.

I'm an athlete — for the first time in my life. I'm learning a lot about my body in the process. It's capable of things I never imagined — not just running long distances, but lifting heavy things. (Metaphorically and literally.) But the "pursuit of wellness" can be, as Christy Harrison argues, such a trap. I see the disordered eating practices; I see the body dysmorphia; I see the adoption of questionable technologies, the ingestion of questionable substances — all because The Internet suggests it'll "enhance performance." For all the talk of "learning to trust your body," I see the ways in which fitness technologies want you instead to trust the algorithms and the metrics that tell you when your "body battery" or stress levels are high, when your VO2Max or your RHR or your 5K predicted time is too low. I see the ways social media influencers promote dubious beliefs and practices; I see how hard it is to wade through the dis- and misinformation online.

The Wellness Trap draws in part on the work of my friend Mike Caulfield — the "four move" method of fact-checking the Web he calls SIFT: Stop; Investigate the source; Find trusted coverage; and Trace claims back to the original. Harrison argues that wellness culture is particularly adept in peddling conspiracy theories; but the response shouldn't be to "do your research" so you can debate or debunk the misinformation. Rather,

SIFT is meant to help people think twice before reflexively sharing or acting upon unverified information. The process involves quickly moving away from the actual content of the misinformation and focusing on the context, so that you're not wasting precious time trying to dissect dubious sources — because that’s exactly what peddlers of disinformation want you to do. 'The goal of disinformation is to capture attention, and critical thinking is deep attention,' Caulfield wrote in 2018. 'Whenever you give your attention to a bad actor, you allow them to steal your attention from better treatments of an issue, and give them the opportunity to warp your perspective.' So instead of doing a deep dive into misinformation to try to understand it from the inside — which is what we might traditionally view as critical thinking — you're better off seeking out other, more credible sources to put the information into context.

And again, I wonder — particularly in light of my own "pursuit of fitness" but also in light of my writing this newsletter: can you just "dabble" in fitness/food/wellness technology without having your attention stolen, without having your behaviors and body conditioned — conditioned by capitalism, by white supremacy, by ablism, by anti-fat bias, by diet culture?

The pursuit: I have fallen in love with movement; I have discovered a love for my body. I have found solace in the rhythm of my feet running on the road, of my heart racing, in the pushing pushing pushing myself to go faster and farther. I don't want to dismiss the good that it's given me; but I can't to suffer any disillusions that it's "fixed" the things about me that are broken — that is, the grief and anguish I'll carry forever because of Isaiah's death. And I worry that if I do stop moving by body so much, I'll find myself stuck with my thoughts again and stuck in a place of despair. A wellness trap indeed.