The Extra Mile

A couple of weeks ago I complained – half jokingly and entirely straight-faced – about the lack of innovation in dental technology. But I confess, I neglected to mention the technological upgrade I did actually experience in the dental chair: being fitted for a mouth guard – a process that did not entail biting into a tray filled with alginate and holding the sticky gelatin in my mouth for 30 minutes, trying calmly to breathe through my nose and not gag. Instead, my dentist took digital impressions, which was still fairly invasive and annoying – a giant camera shoved in my mouth to capture the topography of my teeth – but, importantly, did not involve that terrible sensation of ooze going down the back of my throat.

My new mouth guard arrived last week. When I slide it in each night before bed, I feel like I'm heading to sleep prepped for a REM-state boxing match. But hey, I am no longer grinding my teeth all night. (Go figure, I grind my teeth. Maybe I'm stressed or something?) And as such, I am actually sleeping so much better.

This is, I will admit, a "win" for health technology... except for the part where someone along the way clearly sold my dental data, and I am now inundated with ads on Instagram for various gadgets to clean said mouth guard.

"Bro Summer Waits For Us All," writes Kelsey McKinney in Defector, making the case for embracing good "bro" vibes, along with community, care, and some light roughhousing. Yeah, I don't know about that either.

But it's certainly feeling like summer is here – here in the northern hemisphere at least. I've gotten up at 5am for the past few weekends, trying to get my long run (Saturday) and long ride (Sunday) in before it gets too hot. We're experiencing a "heat dome" or something this weekend. (See also: "Why are we so obsessed with morning routines?" asks Vox.)

Summer also means that Rusty Foster, of Today in Tabs fame, is off on his trek along the Appalachian Trail; and if the call for "bro summer" didn't make you choke up, his essay "Never Going Back" surely will.

Elsewhere in hiking (and biking), Laura Killingbeck weighs in on the "Man or Bear" meme in Bikepacking.com. And Scientific American explains why bears – not the most dangerous apex predator [side-eye, "man"] but apex predator nonetheless – are "friend-shaped."

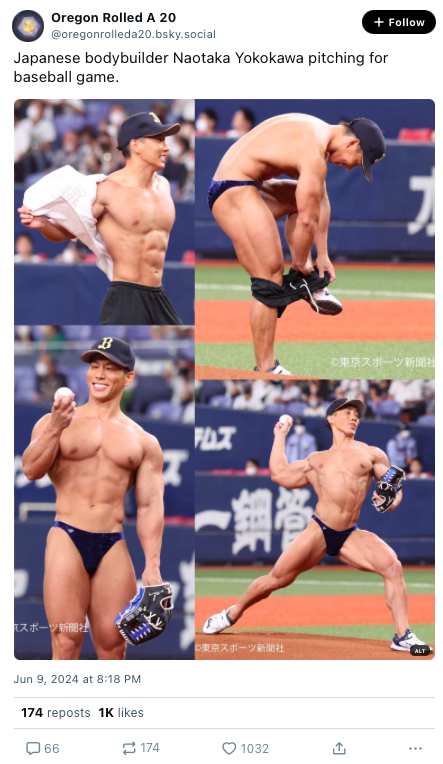

Speaking of the good vibes of "bro summer":

In other sports news: "The Multimillion-Dollar Scandal Rocking Pickleball." "These two Oakland teens could be the future of American weightlifting."

Kin and I watched Andrew McCarthy's documentary Brats the other night.

I've never really been a big McCarthy fan – not a big fan of the actor, not a big fan of the characters he's best known for. That said, there was something wonderfully vulnerable about him in this film – his exploration of how the framing of "the Brat Pack" in a 1985 article in New York Magazine sort of destroyed him, professionally and psychologically. He interviews some of the other actors associated with (we can't really say "members of") the group, many of whom he hasn't seen or spoken to in thirty-some-odd years.

I'm absolutely the target demographic for this film, so a "thumbs up" from me will come as no surprise. And if you're my age, you're probably going to watch this film, because – as Rob Lowe (of all people) reminds McCarthy – the Brat Pack mean a lot to us. The movies associated with the Brat Pack, both explicitly and tangentially – St. Elmo's Fire, The Breakfast Club, Pretty in Pink, The Outsiders – mean a lot to us.

If The Breakfast Club was really just a group therapy jam for 80s high schoolers – for the high schoolers on screen and in the movie audience – McCarthy's conversations with his peers might function as another therapy session for that same group now – GenX on screen and off.

We are getting old – Emilio Estevez has become the absolute spitting image of his father, Martin Sheen. So perhaps, we do think more about legacy. Perhaps we think differently about longevity.

A lot of the recent fuss about longevity – at least as I've been following the narrative here in my work – comes from (and is backed by) our generation's aging tech entrepreneurs, many of whom do see themselves as powerful stars in their own right. Andreessen. Musk. You know the type. But these men all want to sell a product, a procedure, a gadget. Actors sell something too, of course – an image, a story, a piece of the zeitgeist. Capital, big C, little c, cultural, etc. Tech entrepreneurs, by and large, might have (had) power/money/zeitgeist capital; but they surely lack the kind of introspection, reflection, and curiosity that the actors in Brats engage in, at least as interlocutors with McCarthy. I mean, who knew that Demi Moore was so very, very wise?

I did say I'd write about AI, didn't I.

Really, it's intelligence I've been thinking about lately, as I've been reading Zoë Schlanger's new book The Light Eaters: How the Unseen World of Plant Intelligence Offers a New Understanding of Life on Earth. (Side-note 1: get you a friend whose book recommendations you always follow. For me, that's Rose Eveleth, who tipped me off to The Light Eaters, as well as to the other book I'm in the middle of, The Other Olympians.)

Schlanger's book chronicles the debates within botany about recent discoveries surrounding plant behavior and plant intelligence – indeed, to use either of these words, "behavior" and "intelligence," remains controversial in the field. (Behavior-as-thinking – we're back in Skinner territory again, aren't we?)

The idea that plants have any sort of consciousness runs counter to long-held beliefs. Botanists seemed to double-down on these beliefs, particularly in light of the publication in 1973 of The Secret Life of Plants, a bestselling (but largely pseudoscientific) book that claimed, among other things, that plants liked to listen to classical music and could even sense human thoughts. In many ways, the book, Schlanger argues, held the field of botany back for decades, as many scientists risked professional ostracism if they pursued actual research exploring any possibility of a plant intelligence.

What do we mean, Schlanger asks, by "intelligence"? What behaviors indicate that an organism, plant or otherwise, is "thinking"? How does one "think" without a nervous system, without a brain? Some of the reasons why we've answered these questions in such a way to deny plant intelligence can be traced, of course, to ancient Greece and to the Aristotelian insistence that thinking is the purview solely of Man. It's a particular kind of thinking too that is privileged in this definition: rationality.

And it's that form of "thinking," of "intelligence" that is privileged in the discussions about artificial intelligence. It’s actually an inferior, or at least grossly limited version of intelligence, if it’s intelligence at all — the idea that entities, animal or machine, are programmed, coded. It’s so incredibly limiting.

But, as Schlanger points out, intelligence has always been weaponized. We have long withheld the label from certain human groups — Black people, Jewish people, women, and so on — in order to withhold legal rights. To grant machines intelligence is to grant machines political power — the very legal power that we continue to deny the more-than-human world but are so ready to grant to corporations.

Schlanger seems keen to see the definition of “intelligence” expand so that the field of botany can more fully account for the beauty and mystery and complexity of plant life – an intelligence, she suggests, that is obviously radically different from our own. But she recognizes too that the skepticism of many scientists towards some of this new research is, in part, simply how science works. Indeed, it's one of its strengths – science does not immediately adopt every new thesis as truth; it takes more than a press release or even a peer-reviewed paper to challenge the dominant theoretical paradigm.

And that's quite different from computer science, which is so very much not a science, despite the name. Computer scientists – sorry, not scientists – leap into every proposed shift in hardware and software frameworks with full-throated fervor, even if, as Mike Caulfield noted in response to last week's Apple PR event, there's not really a there there.

More related reading: "What's in a name? "AI" versus "Machine Learning" by Dave Karpf. "The Work of Art" by L. M. Sacasas.

(Side-note 2: I often feel obligated to share stories about Wyoming and techno-politics, even when they're dumb (especially when they're dumb): "An AI Bot Is (Sort of) Running for Mayor" of Cheyenne, reports Wired.)

(Side-note 3: What the fuck is wrong with Wired? I mean, I know the answer. But here's a headline to a Steven Levy story – "If Ray Kurzweil Is Right (Again), You’ll Meet His Immortal Soul in the Cloud" – and I'd very much like to know when Kurzweil was right the first time? According to Levy, Kurzweil was right when he predicted that computers would achieve human-level intelligence by 2029. But since neither the date nor the achievement have come to pass... I don't know. But see what I mean about not-a-science?)

And finally, some food and food technology news: "How the Fridge Changed Flavor" by Nicola Twilley. Three flavors of spicy ramen have been recalled in Denmark for being too spicy. The best way to cut an onion, thanks to computer modeling. Why did the cocaine in Coca-Cola become "a problem"? The answer will not surprise you. Also not surprising, the violence of bananas and imperialism: a jury ordered Chiquita Banana to pay $38 million to the families of farmers and other civilians murdered in Colombia between 1997 and 2004 by a paramilitary group on its payroll. The Atlantic on "The Death of the Dining Room" – eating spaces are shrinking, and we are "designing loneliness into American floor plans." The technologies of loneliness; the infrastructure of loneliness. No intelligent houseplant is gonna fix that shit.

Thanks for being a paid subscriber to Second Breakfast. Your support means a lot – I mean, it makes this whole thing [gestures broadly] possible for me right now.