What We Talk about When We Talk about AI in Education

What do folks mean when they talk about AI in education? Most of the time – and I'm certainly at fault here too – no definition or description of AI is even offered. You’re supposed to just known what AI means, what it does – or at the least, you’re supposed to know the story. (Pick a story – one with AI heroes or with AI villains.)

One could argue, I suppose, there’s little room for explanation because it's such a complicated topic, and a lengthy technical accounting would, if nothing else, really bog down the prose. But there's so much hand-waving and word-play, such computer-enhanced verbosity on the subject, the problem obviously isn’t a concern for word count. Talk about AI is clearly meant to inspire awe, not foster understanding.

Indeed, even the coining of the phrase was a bit of a sales pitch. As computer scientist John McCarthy recalled in a 2011 interview, when he was organizing what would become the field's foundational Dartmouth Summer Research workshop, to be held in 1956, "I introduced the term of artificial intelligence ... when I wrote the proposal. I had to think of a name to call it and I called it artificial intelligence. Now, later Donald Michie used the term machine intelligence and my opinion is that that was a better choice." That is, the phrase "artificial intelligence" wasn't a label chosen to describe a science; it was a clever (but inaccurate) turn of phrase, meant to catch the eye of a philanthropic funder.

That the phrase continues to be used as shorthand to lump together a number of different very research areas within and beyond computer science -- natural language processing, machine learning, machine perception, predictive analytics, computational linguistics, expert systems, neural networks, and robotics, just to name a few -- demonstrates how "artificial intelligence" signals something very powerful, all while obfuscating the specifics of these technological and methodological underpinnings. "Artificial intelligence" is a phrase that remains useful (to some people, at least) perhaps because its meaning is overdetermined.

What we mean when we talk about AI in education is necessarily ideological. That means AI means what you want it to mean, more than what the technical specifications mean it can do; and it means AI what a very powerful industry wants it to mean (which incidentally means you’re giving it a helluva lot of power when you say “this changes everything.” And if you claim that it's just a "normal technology.")

In his book Moral Codes: Designing Alternatives to AI, Alan Blackwell defines AI as "the branch of computer science dedicated to making computers work the way they do in the movies." There are technical definitions, if you prefer – the OECD's is eleven pages long, although more a reflection of the political complexities of talk about AI than the technological complexities of AI itself. Blackwell’s definition is shorter, but it underscores that same thing, I’d say: what we have in AI is a cultural artifact as much as a scientific breakthrough, a story as much as a tool.

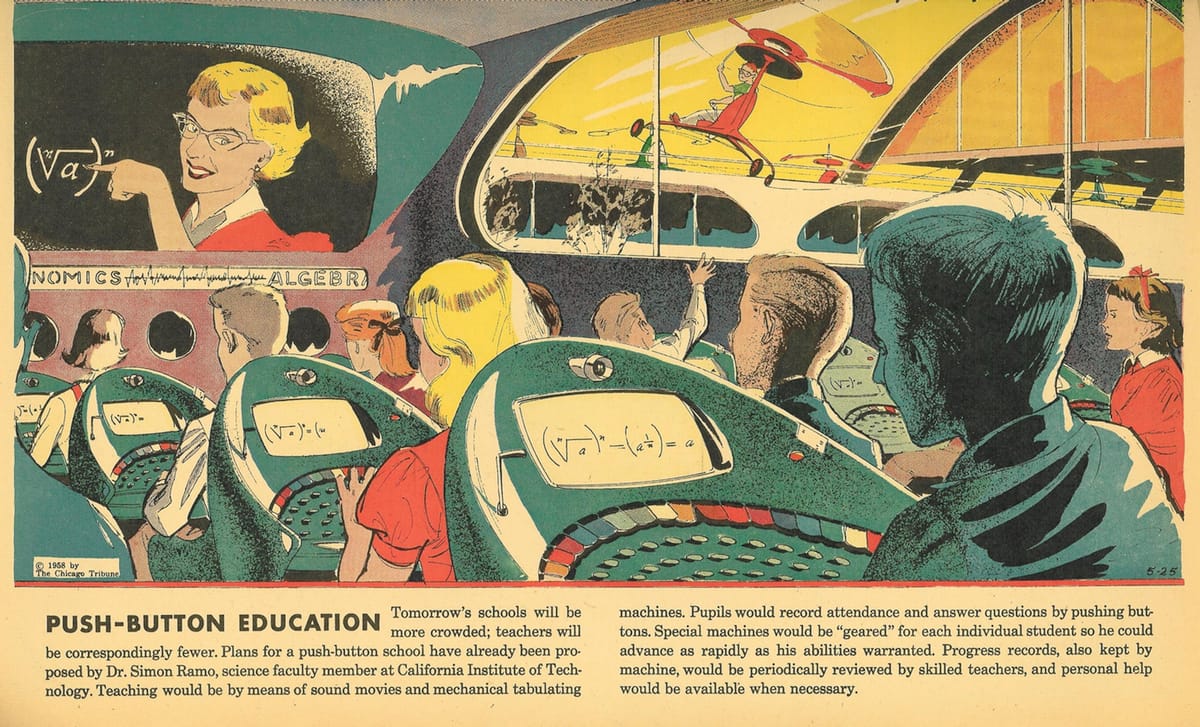

When we talk about AI in education, what tends to get highlighted is the former – a fantasy of robot teachers and push-button classrooms – rather than the latter. When we talk about AI in education, we talk less about what automation and algorithms can do and more about what they will someday be able to do, what we'd like to see the classroom become. What we talk about when we talk about AI in education: talk about AI in education. Stories. Science fiction. Myth. Made-up histories and made-up futures. So many newsletters. My god.

The history of automated teaching is very long, as I will keep repeating until the day I die, it seems. The history of AI is very long too. Nevertheless, a fair number of people seem to believe that AI suddenly appeared in classrooms circa 2022, when ChatGPT 3.5 launched and folks noticed students were submitting AI-generated essays.

In fact, artificial intelligence has been in schools since the dawn of the field. That Dartmouth Summer Research Workshop was held at Dartmouth College after all (not, in case you were confused, in the town of Dartmouth in Devon, England which is, I'm sure, lovely and where Christopher Robin Milne once had a bookstore, according to Wikipedia). Many of those who attended the workshop were professors. (They were all – surprise surprise – men.) But the connection between AI and education goes deeper than that – deeper than the long history of building AI tools for educational purposes, tools like intelligent tutoring systems, automated essay graders, predictive analytics, and so on. As Shayan Doroudi argues in his article "The Intertwined Histories of Artificial Intelligence and Education," many of the early researchers in AI were expressly interested in the inner workings of the mind, that is in human, not just machine learning. Seymour Papert, for example, might be best known to educators for his books Mindstorms and The Children's Machine; but he was also the co-director of MIT’s AI Lab and co-authored with Marvin Minsky the influential and paradigm-breaking book Perceptrons. (He wasn’t at the Dartmouth event, to be clear, but Minsky was.)